In celebration of the publication of Shinobu Hashimoto‘s book Compound Cinematics, this month’s 10 Pieces of Akira Kurosawa article will be all about Akira Kurosawa’s screenwriters.

If you do an IMDb search for “Akira Kurosawa”, he is identified by the system as “writer, Yojimbo”. Similarly, when you look at his filmography on the website, it is his 72 writer’s credits that you see first, and not the 30 films that are considered his directorial canon. Kurosawa was indeed an accomplished and award winning screenwriter, yet when it came to his own films, he usually preferred to write with a team. Only the first four and the last three of his films were written solo, while the rest featured a rotating group of screenwriters.

But who were these screenwriters? Let’s find out!

Keiji Matsuzaki

1 screenplay for Kurosawa (uncredited), 1946

Keiji Matsuzaki (1905-1974) was one of Kurosawa’s early producers. He produced the director’s debut film Sanshiro Sugata (1943), as well as co-producing the collaborative Those Who Make Tomorrow (1946), which Kurosawa begrudgingly worked on for Toho. Matsuzaki similarly handled production for Kurosawa’s first post-war film, No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), which was the first film that Kurosawa co-wrote with people. It is precisely during the production of No Regrets for Our Youth that Matsuzaki, who had started his career as a screenwriter in the early 1930s before becoming a producer, ended up helping with the script.

In some ways you could even say that No Regrets for Our Youth was Matsuzaki’s story: it was he who originally suggested the topic, and he also conducted much of the research. He was furthermore able to offer valuable first hand insight as a former student of Yukitoki Takigawa, the professor on whom the film is partly based on. He is not credited in the film as a screenwriter, but Matsuzaki was partly involved with the writing process as well, even if the bulk of the actual writing was done by Kurosawa and the film’s primary screenwriter, Eijirō Hisaita (see below), whom Matsuzaki had originally introduced to Kurosawa.

Sometime after No Regrets for Our Youth, Matsuzaki left Toho studios where he had worked for most of his career, and moved to the the rival Tokyo based Toei company. There, Matsuzaki continued as a producer until the late 50s but his path never professionally crossed with Kurosawa’s again.

Eijirō Hisaita

4 screenplays for Kurosawa, 1946-1963

Playwright-turned-screenwriter Eijirō Hisaita (1898-1976) was Kurosawa’s first official screenwriting partner. The two created No Regrets for Our Youth together with Keiji Matsuzaki as described above, and later Hisaita also penned The Idiot (1951) with Kurosawa, as well as being part of a larger screenwriting team for The Bad Sleep Well (1960) and High and Low (1963).

Playwright-turned-screenwriter Eijirō Hisaita (1898-1976) was Kurosawa’s first official screenwriting partner. The two created No Regrets for Our Youth together with Keiji Matsuzaki as described above, and later Hisaita also penned The Idiot (1951) with Kurosawa, as well as being part of a larger screenwriting team for The Bad Sleep Well (1960) and High and Low (1963).

In addition to his work for Kurosawa, Hisaita also wrote a number of films for other filmmakers, including several for Keisuke Kinoshita. His literary works were also adapted for the big screen, most notably Women of the Night which was directed by Kenji Mizoguchi in 1948.

Hisaita continued his writing career all the until his death in 1976, with his last published work coming out in 1975, at the age of 77. Unfortunately, none of Hisaita’s works have been translated into English, nor indeed seemingly into any other western language.

Keinosuke Uekusa

2 screenplays for Kurosawa, 1947-1948

Of the hundreds of people that Kurosawa worked with during his career, playwright and novelist Keinosuke Uekusa (1910-1993) was his very first professional acquaintance. Not that he probably realised it when they first got together. The two met at around the age of six.

Of the hundreds of people that Kurosawa worked with during his career, playwright and novelist Keinosuke Uekusa (1910-1993) was his very first professional acquaintance. Not that he probably realised it when they first got together. The two met at around the age of six.

With only 18 days separating the two men’s births (Uekusa was the senior), Kurosawa and Uekusa attended the same elementary school in Tokyo. And not only were they classmates, but they were also good friends, brought together by their sensitive natures and outsider status. In his autobiography, Kurosawa describes the young Uekusa and himself as “crybabies”, jokingly remarking that this never really changed when they grew up, only that Uekusa would grow up to be a “romantic crybaby”, and Kurosawa a “humanist crybaby”. The friendship between the two lasted their lifetimes.

Kurosawa and Uekusa first worked together professionally in Kajirō Yamamoto’s 1938 film Tojuro’s Love, although neither of them did so in a screenwriting capacity. Instead, Kurosawa handled duties as a chief assistant director as well as a dubbing supervisor (his only official sound department credit), while Uekusa had a minor role as an actor.

It was almost ten years later, with Kurosawa now an up-and-coming director and Uekusa a similarly promising playwright and screenwriter, that the two worked together properly for the first time. The occasion was Kurosawa’s second co-scripted film One Wonderful Sunday (1947), which was immediately followed by Kurosawa and Uekusa writing Kurosawa’s next film, Drunken Angel (1948). Their second collaboration would, however, remain their last film together, as Uekusa then drifted to other forms and topics.

Outside of his work for Kurosawa, Uekusa worked for both film and stage. As a playwright, he was in demand, although none of his plays appear to have been published in English or other western languages. As a screenwriter, it seems that Uekusa could pick and choose his projects and as a result he had a very varied career, writing everything from musicals to animated films, a total of around thirty films.

Senkichi Taniguchi

1 screenplay for Kurosawa, 1949

Film director and screenwriter Senkichi Taniguchi (1912-2007) was another good friend of Kurosawa’s. The two met in their assistant director days in the mid-1930s, and during a six-year time period between 1947 and 1953 no fewer than eight films were released where the two shared credits. Five of those were directed by Taniguchi from screenplays that he and Kurosawa wrote together, while one film had the reversed setup, with Taniguchi and Kurosawa adapting a play by Kazuo Kikuta into Kurosawa’s 1949 film The Quiet Duel. Taniguchi also served as an associate producer for Kurosawa’s Stray Dog (1949). Yet, for some reason the partnership ended following Taniguchi’s 1953 My Wonderful Yellow Car, and although the two men remained in touch, they never worked together again.

Film director and screenwriter Senkichi Taniguchi (1912-2007) was another good friend of Kurosawa’s. The two met in their assistant director days in the mid-1930s, and during a six-year time period between 1947 and 1953 no fewer than eight films were released where the two shared credits. Five of those were directed by Taniguchi from screenplays that he and Kurosawa wrote together, while one film had the reversed setup, with Taniguchi and Kurosawa adapting a play by Kazuo Kikuta into Kurosawa’s 1949 film The Quiet Duel. Taniguchi also served as an associate producer for Kurosawa’s Stray Dog (1949). Yet, for some reason the partnership ended following Taniguchi’s 1953 My Wonderful Yellow Car, and although the two men remained in touch, they never worked together again.

Taniguchi was best known for his action and entertainment films. Although his output began to dwindle after 1965 due to the problems of the Japanese film industry, his career continued until the mid 70s, with the then 63-year-old director’s final film being the fairly little known 1975 Asante Sana, written by Masato Ide (more of whom below). Although different sources give different filmogrpahies, Taniguchi directed altogether around 45 films in his career, thirteen of which starred Toshirō Mifune, including Mifune’s screen debut in the 1947 Snow Trail (co-written with Kurosawa).

Interestingly enough, probably the most widely seen work directed by Taniguchi is actually a Woody Allen film. In 1965, Taniguchi completed a a spy comedy thriller titled International Secret Police: Key of Keys, which was already the fourth instalment in a series of films parodying the James Bond franchise that had had its film premiere in 1962. Proving that derivative works can never be taken far enough, young and upcoming Woody Allen then literally took Taniguchi’s film as the basis for his own directorial debut titled What’s Up, Tiger Lily?. Allen did not reshoot the film but he did rewrite it, dubbing all the characters and changing the story from a fairly general spy plot into a farce revolving around a stolen egg salad recipe. What you basically have as the result is Taniguchi’s film (re-edited) and a group of Hollywood actors dubbing the scenes with puns and jokes provided by Allen.

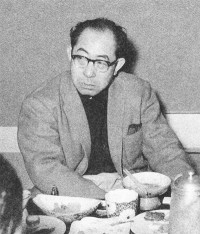

Ryūzō Kikushima

9 screenplays for Kurosawa, 1949-1969

Ryūzō Kikushima (1914-1989) is something of an enigma. In the late 1940s Kikushima was a young writer who had never written a screenplay before, yet somehow his path crossed with Kurosawa’s, who recognised something in him. The director decided to bring the writer in for a film that he was developing based on an unpublished novel that Kurosawa had written. And so, Kikushima got his first job as a screenwriter, helping Kurosawa put together the screenplay for what would become what is often labelled Kurosawa’s first major film, Stray Dog (1949).

Ryūzō Kikushima (1914-1989) is something of an enigma. In the late 1940s Kikushima was a young writer who had never written a screenplay before, yet somehow his path crossed with Kurosawa’s, who recognised something in him. The director decided to bring the writer in for a film that he was developing based on an unpublished novel that Kurosawa had written. And so, Kikushima got his first job as a screenwriter, helping Kurosawa put together the screenplay for what would become what is often labelled Kurosawa’s first major film, Stray Dog (1949).

The two would work again on Kurosawa’s next film, Scandal (1950), after which Kikushima contributed also to Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958), The Bad Sleep Well (1960), Yojimbo (1961), Sanjuro (1962), High and Low (1963) and Red Beard (1965), primarily working with Kurosawa’s expanded screenwriting group, with the exception of Yojimbo which Kikushima and Kurosawa wrote as just a two-man team. After the founding of Kurosawa Productions, Kikushima also served as an executive for Kurosawa’s production company.

When Kikushima was not working for Kurosawa, he wrote critically acclaimed screenplays for other directors. These include Mikio Naruse’s When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960), Kon Ichikawa’s Princess from the Moon (1987), Hiroshi Inagaki’s Arashi (1956) and The Birth of Japan (1959), as well as Minoru Shibuya’s The Unbalanced Wheel (1957) and Seiji Maruyama’s There Was a Man (1955), the latter two of which won Kikushima prestigious Blue Ribbon Awards. In the late 1960s, Kikushima also worked with Kurosawa on his two Hollywood screenplays, Runaway Train and Tora! Tora! Tora!. It was during Kurosawa’s disastrous production of the latter that the two men fell out completely, with Kikushima resigning from his post at Kurosawa Productions and the two men never working, or apparently even speaking, with one another again.

Despite his central role in no less than nine of Kurosawa’s films, the screenwriter goes entirely unmentioned in Kurosawa’s 1981 autobiography. Kurosawa’s assistant Teruyo Nogami mentions him just once in passing in her memoir, and while Shinobu Hashimoto‘s screenwriting memoir has an entire section titled “Ryuzo Kikushima”, he actually writes almost nothing at all about the man. Similarly, while both Stuart Galbraith and Hiroshi Tasogawa mention Kikushima on a number of occasions in their books, no clear picture of the man emerges.

The statistics, then, have to speak for Kikushima. According to the Japanese Movie Database, Kikushima wrote close to 90 filmed screenplays in a career spanning 50 years. Around 20 other films were based on his writings. 8 producer’s credits. Multiple awards.

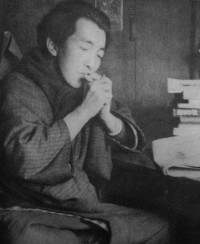

Shinobu Hashimoto

8 screenplays for Kurosawa, 1950-1970

Of the ten screenwriters that Kurosawa worked with, Shinobu Hashimoto (born 1918) is the only one still alive. The now 97-year-old screenwriter’s book Compound Cinematics: Akira Kurosawa and I was published in English about a month ago, and it is highly recommended reading for anyone interested in Kurosawa’s working methods.

Of the ten screenwriters that Kurosawa worked with, Shinobu Hashimoto (born 1918) is the only one still alive. The now 97-year-old screenwriter’s book Compound Cinematics: Akira Kurosawa and I was published in English about a month ago, and it is highly recommended reading for anyone interested in Kurosawa’s working methods.

Hashimoto became a screenwriter pretty much by accident. While recovering from tuberculosis at an army rehabilitation centre in 1941, he came across a film magazine that included a screenplay. Thinking that he could easily write something at least as good, Hashimoto contacted the celebrated director and screenwriter Mansaku Itami, whose informal student he soon became. After Itami’s death in 1946, Hashimoto was introduced to director Kiyoshi Saeki who in turn knew Kurosawa and promised to pass one of Hashimoto’s screenplays to the already famous director. This screenplay would soon become Rashomon (1950).

Just like Ryūzō Kikushima, Hashimoto had no previous films to his credit when he started working for Kurosawa. But he was clearly very talented. He returned to write with Kurosawa on Ikiru (1952) and Seven Samurai (1954), where he could be described as the lead writer, and then became part of Kurosawa’s expanded group of screenwriters for the next five years, taking part in the writing of Record of a Living Being (1955), Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958) and The Bad Sleep Well (1960). Although apparently feeling that Kurosawa’s change in screenwriting methods after the tight but time consuming collaborations of Ikiru and Seven Samurai were not optimal, he was there when Kurosawa needed him, first returning to help write Dodesukaden (1970) with Kurosawa and Hideo Oguni, and then leveraging his influence to help finance Kagemusha (1980).

Hashimoto’s talents were also required elsewhere. His screenwriting career lasted until the mid-80s and comprised of over 70 films. Due to health problems he has written less in his later years, but some of his earlier screenplays have been remade, including I Want to be a Shellfish (2008) and Samurai Rebellion (2013). Other films that he wrote include Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962) and Kihachi Okamoto’s Sword of Doom (1966).

Hideo Oguni

12 screenplays for Kurosawa, 1952-1985

Hideo Oguni (1904-1996) was the screenwriter that Kurosawa most often worked with, and also one that was there throughout almost all of his career. A cursory look at Kurosawa’s film credits would suggest that the first time that Kurosawa and Oguni got together was on Ikiru (1952), but in fact their collaboration goes back to a time before Kurosawa had even yet made his directorial debut.

Hideo Oguni (1904-1996) was the screenwriter that Kurosawa most often worked with, and also one that was there throughout almost all of his career. A cursory look at Kurosawa’s film credits would suggest that the first time that Kurosawa and Oguni got together was on Ikiru (1952), but in fact their collaboration goes back to a time before Kurosawa had even yet made his directorial debut.

As a prolific young screenwriter, Oguni had started his career at PCL (later Toho) in the early 1930s, writing mainly action films and comedies for various directors. Kurosawa, who joined the studio as an apprentice in 1936, admired Oguni’s skills with structure and characters, and as the two men happened to be near neighbours, a rapport developed. In 1942, Kurosawa and Oguni penned together a screenplay titled Three Hundred Miles Through Enemy Lines which would have been Kurosawa’s directorial debut had it not been deemed too costly by Toho. The film was later directed by Kazuo Mori for a 1957 release.

Although Oguni did not appear as a writer in official capacity on any of Kurosawa’s early films, the director often sought the screenwriter’s advice when working on new scripts. Finally, as he was starting work on Ikiru (1952), Kurosawa announced that Oguni’s advice alone would no longer be needed and what would be requested instead was full participation. Even then, however, Oguni at first remained in something of an advisory role, with Kurosawa and Shinobu Hashimoto taking care of the actual writing on Ikiru and Seven Samurai (1954) while Oguni functioned as their “command tower”, sitting with his back turned to the writers and going through the new pages as they were written, either accepting or rejecting them. Starting with Record of a Living Being (1955), however, also Oguni picked up the pen.

Between Ikiru and Ran (1985), Oguni was an integral part of all but three of Kurosawa’s films, sitting out only Yojimbo (1961), Dersu Uzala (1975) and Kagemusha (1980). Together with Kikushima, he was also part of the writing process on Runaway Train and Tora! Tora! Tora! in the late 1960s, neither of which Kurosawa ultimately ended up directing. He fell out artistically with Kurosawa during the writing process for Ran in the mid-70s, and did not actually see the screenplay to its completion.

Oguni’s largest contribution to Kurosawa’s narrative style is perhaps also the most praised and criticised aspect of the director’s style of storytelling: his overt humanism. Meanwhile, it is Oguni’s first film with Kurosawa, Ikiru (1952), which has the most famous anecdote of his influence on Kurosawa’s writing. Oguni was late to get to the bed and breakfast that Kurosawa had chosen for the writers, and as he arrived the two others had already put together 40 pages for the screenplay. Oguni’s reaction to the completed pages was negative and Kurosawa reportedly got so mad that he tore up the script and blamed Oguni’s late arrival for their failure. But Oguni wasn’t there simply to offer criticism. Most importantly, he suggested that the death of the main character should be moved to the middle of the film, an idea that gave birth to the film’s famous structure. Later on, Kurosawa would describe Oguni as his navigator who pulls him back into course when he goes astray.

In addition to his contribution to Kurosawa’s films, Oguni worked on around one hundred films during a career spanning more than half a century. His non-Kurosawa films include Hiroshi Inagaki’s samurai film Ambush (1970) which features Toshirō Mifune as Yojimbo, Koji Shima’s science fiction film Warning from Space (1956), Heinosuke Gosho’s postwar drama Where Chimneys are Seen (1953), and Mikio Naruse’s A Tale of Archery at the Sanjusangendo (1945).

Masato Ide

3 screenplays for Kurosawa, 1965-1985

Screenwriter Masato Ide (1922-1989) was first brought in for Red Beard (1965), and he can be called the final addition to Kurosawa’s regular screenwriting team. When he joined Kurosawa, Kikushima and Oguni, Ide already had almost 15 years of experience as a screenwriter, during which period he had written close to 50 filmed screenplays, many of which had been big hits for Toho. It was also not the first time that the names of Kurosawa, Kikushima and Ide appeared together, for back in 1955 Kurosawa and Kikushima had adapted Ide’s debut novel into a screenplay for Akira Mimura’s film The Lost Garrison. But it was the first time that they were writing together.

After graduating in 1941, Ide had at first been an elementary school teacher, but by the mid-1940s he was working at Shintoho studio’s administrative and production planning division. During this time he wrote the above mentioned debut novel and then in 1949 took part and ended up winning the first prize in Shintoho’s screenwriting contest. This opened a career for him as a screenwriter, and Ide began writing screenplays first for Shintoho, and after a few years also for Japan’s other leading film studios. In addition to Red Beard, Ide also worked on the screenplays for Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985).

Ide’s best known scripts outside of Kurosawa are probably The Sea Is Watching director Kei Kumai’s The Sands of Kurobe (1968) and Kurosawa’s former assistant director Yoshitarō Nomura’s films The Demon (1978) and The Scarlet Camellia (1964), the latter of which was released just a year before Red Beard and like Kurosawa’s film based on a novel by Shūgorō Yamamoto.

In a prolific career which lasted until his death in 1989, Ide provided screenplays for a total of close to seventy films.

Yuri Nagibin

1 screenplay for Kurosawa, 1975

Yuri Nagibin (1920-1994) was a Russian screenwriter, novelist and journalist who worked with Kurosawa on the screenplay for the director’s Soviet financed 1975 film Dersu Uzala. In her memoir, Teruyo Nogami describes how this wasn’t an entirely straightforward process: Nagibin originally insisted on a more dramatic and action filled treatment of the story, which was in stark contrast with Kurosawa’s first drafts that were bleak and focused on existential questions. When Kurosawa and Nagibin sat down together in October 1973 to discuss their differences, the result was something that the other preproduction crew members called the “Russo-Japanese War”. In the end, and after several days, Kurosawa prevailed and was able to keep his approach to the film, although the final version is said to be less bleak than his early drafts, which had been written fairly soon after his attempted suicide.

Yuri Nagibin (1920-1994) was a Russian screenwriter, novelist and journalist who worked with Kurosawa on the screenplay for the director’s Soviet financed 1975 film Dersu Uzala. In her memoir, Teruyo Nogami describes how this wasn’t an entirely straightforward process: Nagibin originally insisted on a more dramatic and action filled treatment of the story, which was in stark contrast with Kurosawa’s first drafts that were bleak and focused on existential questions. When Kurosawa and Nagibin sat down together in October 1973 to discuss their differences, the result was something that the other preproduction crew members called the “Russo-Japanese War”. In the end, and after several days, Kurosawa prevailed and was able to keep his approach to the film, although the final version is said to be less bleak than his early drafts, which had been written fairly soon after his attempted suicide.

During a literary career which started in the early 40s and lasted until his death in 1994, Nagibin was credited in over 40 films, first as the author on whose works films were based, and later starting in 1958 increasingly often as a screenwriter.

Ishirō Honda

2 screenplays for Kurosawa (uncredited & uncertain), 1990-1993

Ishirō Honda (1911-1993) is best known as the director of several popular monster, special effects and war films, most famously in the Godzilla film series. He was also Kurosawa’s lifelong friend, with the two having first met during their assistant director days in the 1930s. Honda worked as Kurosawa’s assistant director on the 1949 Stray Dog and later served as a close assistant and second unit director for Kurosawa’s final films starting with Kagemusha. He is also often listed as an uncredited screenwriter on Dreams (1990) and Madadayo (1993), although finding an authoritative confirmation for this is difficult. Whatever his actual influence was on the screenplays, his presence was extremely important for Kurosawa, especially towards the twilight of the director’s life and career.

Ishirō Honda (1911-1993) is best known as the director of several popular monster, special effects and war films, most famously in the Godzilla film series. He was also Kurosawa’s lifelong friend, with the two having first met during their assistant director days in the 1930s. Honda worked as Kurosawa’s assistant director on the 1949 Stray Dog and later served as a close assistant and second unit director for Kurosawa’s final films starting with Kagemusha. He is also often listed as an uncredited screenwriter on Dreams (1990) and Madadayo (1993), although finding an authoritative confirmation for this is difficult. Whatever his actual influence was on the screenplays, his presence was extremely important for Kurosawa, especially towards the twilight of the director’s life and career.

For the sake of completeness, let it also be mentioned that the composer Fumio Hayasaka (1914-1955) is another name that you will come across if you go through the screenwriting credits for Kurosawa’s films. Although he is mentioned by some as an uncredited screenwriter for Record of a Living Being (1955), Hayasaka was never part of the actual writing process. Instead, the film is based on a conversation that Kurosawa and Hayasaka had, with the originating idea coming from Hayasaka. The extremely talented composer, who scored eight of Kurosawa’s films between 1948 and 1955, sadly died of tuberculosis during the post-production of Record of a Living Being.

I think of Oguni as Kurosawa’s editor par excellence.