“It was a hot day. Even now, I cannot forget the searing heat of that day.”

“It was a hot day. Even now, I cannot forget the searing heat of that day.”

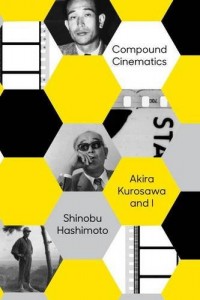

More or less thus begins Shinobu Hashimoto‘s Compound Cinematics: Akira Kurosawa and I, a book which despite its rather unfortunate cover design is not a beekeeper’s manual or a strategy board game, but in fact a real and proper book about a rather interesting part of film history. Written by Akira Kurosawa‘s longtime co-screenwriter, it is the first book to concentrate on Kurosawa’s collaborative screenwriting practices. Originally published in 2006 in Japan, it has now been made available in English by Vertical Inc and it has definitely been worth the wait.

As the quote above illustrates, Compound Cinematics shares something with the films that it discusses. It is far from a lifeless technical account of events, or even a standard linear memoir. At the age of 90, Hashimoto is still a screenwriter and storyteller, and in many ways his book reflects that. Although it is highly self-referential and sometimes moves in circles while anticipating something that would happen only much later, the book has a clear structure which largely conforms to the kishōtenketsu structure that the author frequently refers to, and the book in fact strongly resembles a first person novel (shishōsetsu), a typical genre of Japanese literature which is grounded in autobiographical details. This is not to say that Compound Cinematics is a work of fiction, but it definitely seems to frame itself as one, and the result is a marvellously clever work which is an absolute pleasure to read, no doubt also very much thanks to the book’s translator Lori Hitchcock Morimoto.

So, what is Compound Cinematics? At its core, it is the story of a boy from a poor rural family who by chance comes in contact with a famous benefactor (Mansaku Itami) who trains him and unknowingly prepares him for another meeting that changes the boy’s life.

Mr. Kurosawa appeared right away. He was astoundingly tall. I especially remember his graceful, deeply-chiseled features and the red sweater he wore. I was thirty-one, and since he was eight years older than me he would have been thirty-nine, and in his hand he held my handwritten draft of Shiyu. Once we were seated across from each other, he pushed my draft forward and began to speak.

“This Shiyu you have written, it’s a bit short, isn’t it?”

“In that case, what if I included ‘Rashomon’?”

“Rashomon?” Mr. Kurosawa cocked his head. It was a momentary blank like an air pocket, but the tense silence didn’t last very long. “Well then, can you add ‘Rashomon’ to this and rewrite it?”

“Yes, I’ll do that.”

Our first meeting ended so simply that it didn’t feel complete. We spoke for only one or two minutes, and then I put my manuscript in my bag, and both Mr. Kurosawa and his wife Kiyoko showed me out when I left.

As I left the residence, however, my regret and shame began.

Why had I said that? Put “In a Grove” and “Rashomon” together?

I had blurted out something that I hadn’t even thought of before, that hadn’t even been in the back of my mind.

Thus began a collaborative relationship which lasted for nine films, or almost a third of Kurosawa’s entire output. And yet, the two men never got together on a personal level. For Hashimoto, Kurosawa appears to have remained an enigma, a distant and somewhat mysterious craftsman-turned-artist whose genius was nevertheless never above criticism.

Consequently, those looking for insights into Kurosawa as a private person must, once again, turn away disappointed. On the other hand, those searching for information about the working methods of Kurosawa’s screenwriting team, their collaborative process of “compound cinematics”, are in for a treat.

Even more than that, Compound Cinematics is the author’s own autobiography that makes use of his work with Kurosawa as a reflective surface with which he can shed light on his own persona and the subjects that he feels strongly about.

Among the things that Mr. Kurosawa said to me, one made a lasting impression.

“Hashimoto, writers have autobiographies, right?”

“Yes, they do.”

“All of them are interesting to read. Because a lot of things happen in a person’s life. But my own autobiography won’t happen until I’ve run out of works to write… That is, I think it’ll be the very last thing I write.”

I also had that impression, so I nodded.

He continued, “That’s why I think of an autobiography as a person’s last testament.”

In his own last testament, Hashimoto is concerned about the future of film as a narrative art form. He argues passionately for a type of collaborative writing which he and Kurosawa employed on films like Rashomon, Ikiru and Seven Samurai. He also calls for a much wider range of films to be produced, suggesting that productions should embrace works of all shapes, forms and lengths, in addition to the traditional two-hour feature.

At the same time, the book is a portrait of Hashimoto himself. What emerges from the pages is a somewhat peculiar man who clearly lives and breathes film but also believes so much in the importance of screenplay that at one point he declares it to be a total waste of time to watch a film whose screenplay you have already read, as they are essentially the same thing. Here also is a man whose name appears in the credits of The Bad Sleep Well but who has apparently neither seen the film nor read the final screenplay, having due to scheduling conflicts left the production before writing had finished, not entirely interested in the story anyway. Neither has he by his own account seen a single Steven Spielberg film since Jaws because he is convinced that the American director could never surpass the brilliance of that work, so spending time with any of his other films would be pointless.

Hashimoto, in other words, comes across as a man of strong opinions and equally resolute convictions. And while you may not agree with everything that he says, and are often left wondering how much of what you read is actual Hashimoto and how much a character created by Hashimoto, it is all very fascinating reading.

Contents

Compound Cinematics is divided into seven sections, starting with a short Prologue (9-14) and progressing onto the book’s five numbered chapters. Chapter One (“The Birth of Rashomon“, 15-40) describes how the author became a screenwriter and how he developed his skills under the informal mentorship of Mansaku Itami, who was coincidentally also something of a father figure for another Kurosawa regular, Teruyo Nogami. Chapter Two (“The Man Called Akira Kurosawa”, 41-140), the longest chapter in the book, explains how Hashimoto ended up working with Kurosawa and describes in detail the creative process that led to the screenplays for Rashomon, Seven Samurai and Ikiru, the three films that the author is understandably most proud of.

Although much shorter than the preceding chapter, Chapter Three (“The Lights and Shadows of Collaborative Screenplays”, 141-176) is the heart and soul of the book where Hashimoto makes his central argument. Here, he describes a major change in how Kurosawa’s team approached screenplays after the production of Seven Samurai. Up until then, Kurosawa’s collaborative screenplays had been written with the time consuming practice of thorough initial preparations and multiple drafts, with each writer carrying different roles — in Ikiru and Seven Samurai, for instance, all of the writing was done by Hashimoto and Kurosawa, while the team’s third member Hideo Oguni acted as a “command tower” who evaluated what was being written and either accepted or rejected the produced pages, not putting a single character on paper himself. Starting with Record of a Living Being, the collaborative process changed to one where everyone wrote simultaneously and in competition with each other, with the goal of producing the film’s final draft in one go. This was a much faster process, but Hashimoto argues that it was also an inherently flawed system which produced inferior screenplays. With a few exceptions, Hashimoto is fairly critical of the majority of Kurosawa’s post-Seven Samurai output, including all of the films that he himself helped to write.

Chapter Four (“Hashimoto Pro and Mr. Kurosawa”, 177-202) discusses Hashimoto’s production company Hashimoto Pro and how he somewhat against his better judgement found himself working again with Kurosawa to get Kagemusha funded. Despite his involvement with the production, Hashimoto is incredibly critical of Kagemusha, as he is of Ran, both of which he considers narrative failures and further examples of the deficiencies in the type of collaborative writing arrangement which Kurosawa adopted after Seven Samurai.

Chapter Five (“What Followed for Mr. Kurosawa”, 203-218) is a short account of Kurosawa’s career after Ran, although in practice Hashimoto only discusses Dreams which he argues is in fact Kurosawa’s best film: “As a filmmaker’s last will and testament, there’s no greater work. … Mr. Kurosawa made two films following Dreams, Rhapsody in August and Madadayo, but since I’d already seen the autobiographical Dreams, which should be considered his testament, I never saw those other two.”

Hashimoto closes the book with an Epilogue (219-251) which looks at the deaths of his screenwriting partners Ryūzō Kikushima, Hideo Oguni and Akira Kurosawa, while reiterating his central argument for the importance of collaborative writing. The section on Kikushima is a particularly strange one as it describes Hashimoto’s visit to the hospital where Kikushima spent his final days. Sitting alone on his bedside, and uncertain whether the immobile Kikushima could even hear or understand him, Hashimoto begins to tell Kikushima about a government supported national film production company which was apparently being planned in the late 60s and aimed to save the declining Japanese film industry. As a testament to how well he sets a scene draws the reader in, while reading the rather lengthy section I madly wanted to grasp Hashimoto’s hand and insist that “No, Mr Hashimoto, this is neither the time nor the place, let the man rest!” And yet, in terms of what Hashimoto wants to communicate, it is exactly the time and place for his monologue. Although less peculiar, the sections on Oguni and Kurosawa are similarly utilised to sum up the argument that Hashimoto has developed throughout the book.

The book finally ends like a Japanese film, with an otherwise blank page displaying the words “The End”.

Conclusion

Compound Cinematics: Akira Kurosawa and I is a fascinating book. Part memoir, part novel, part testament, part screenplay and part argument for a new type of cinema, it is an excellently written and certainly thought provoking account by a man who is partially responsible for at least half a dozen of cinema’s greatest achievements. As a Kurosawa book it gives you much new information, as well as an angle into the director’s works that you may not have considered before.

As a result, Compound Cinematics can be warmly recommended to anyone, regardless of whether you are interested in Kurosawa, Japanese cinema, screenwriting or just a good story. It is a joy to read and a pleasure to think about.

Compound Cinematics: Akira Kurosawa and I is available for purchase from all major bookshops, including Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.de. The book is available in both hardcover and ebook formats.

I’ve just finished this book – I will post a little more on it later, but just to say for now that I concur 100% with Vili’s review. I must admit that based on the cover and title I was expecting something a little heavy going, but I’m delighted to say that it is a terrific book, fascinating and often very moving. Hashimoto seems to be quite a character, and very opinionated (there is no such thing as a 2 and a half star movie in his world – its either a masterpiece or a waste of time). He never pretends to have been Kurosawa’s friend, but he worked intimately with him and his insights are fascinating, as are his very forthright opinions on those AK films he didn’t work on. This is maybe my favourite book on Kurosawa I’ve read and the insights are absolutely invaluable. Essential reading.