In this September’s edition of our Akira Kurosawa film club, we continue travelling with the Man With No Name.

In this September’s edition of our Akira Kurosawa film club, we continue travelling with the Man With No Name.

After having witnessed his debut in Yojimbo and his doppelgänger in A Fistful of Dollars, we are now back in Toshiro Mifune’s shoes, as he portrays the hero we call Sanjuro in Kurosawa’s sequel to Yojimbo, simply titled Sanjuro (or Tsubaki Sanjuro, 椿三十郎, in original Japanese).

Kurosawa had not originally planned to direct a sequel to Yojimbo, but following the film’s massive critical and commercial success, Kurosawa’s film studio Toho asked him to consider the idea. It is not clear whether Kurosawa’s decision was influenced by the fact that he now had some of his own money on the line in the form of his recently founded production company Kurosawa Production, but Kurosawa ultimately agreed with Toho’s request and proceeded to film a sequel, something he hadn’t done since the studio had ordered him to follow his debut film with the 1945 work Sanshiro Sugata Part Two.

Yet, Sanjuro is not a sequel in the traditional sense of the word. Instead of continuing where the previous film had left off, Sanjuro has little direct connection with its predecessor. While the hero remains the same or at least very similar, and although there are some musical, visual and other production elements that wink to the original, the story, the characters, the milieu and most importantly the tone of the second film is very different from Yojimbo. Because of this, Sanjuro is perhaps better thought of as a companion piece that explores a similar territory as its predecessor, although from a different angle.

The story of Sanjuro had in fact originated as a totally different project, something Kurosawa had written for another director, his former assistant director Hiromichi Horikawa, to film. But as that project had folded and Kurosawa was in need of a samurai story, he took the script and reworked it into its new form. And some work was definitely needed. Based on a short story by Shugoro Yamamoto, the original script had featured a samurai hopeless with the sword but quick with his wits, but this obviously did not match the larger than life super samurai established in Yojimbo, and things had to be changed. As with his previous films, Ryuzo Kikushima worked as Kurosawa’s co-writer for the script.

Yamamoto’s original short story appears to be unavailable in English, and he has in fact altogether been very sparingly published in English. This is sad, for although Sanjuro was the first Kurosawa film to be based on Yamamoto’s writing, the following years would see the director drawing frequently from the author’s oeuvre. Both Red Beard and Dodesukaden are based on Yamamoto’s stories, while the contemporary script for Dora-Heita filmed later by Kon Ichikawa, as well as the later posthumously filmed works After the Rain and The Sea is Watching also had their origins in Yamamoto’s books. We will be watching all of these films during the next two years.

As both the story as well as much of the adaptation existed already before it was chosen as a sequel to Yojimbo, it is not surprising that the two stories have little connection with one another. Perhaps more interesting, then, is the shift in tone. While Yojimbo had been funny, it was also dark, gritty and at times grotesque. Sanjuro, in comparison, is much lighter, brighter, relaxed and openly humorous. It is also a more direct samurai film, with less influence from the likes of John Ford and Dashiell Hammett. Sanjuro is in fact perfectly summed up by Stuart Galbraith IV, who in his Kurosawa-Mifune biography writes that it “is a lightweight film, but as lightweight films go, it is something of a masterpiece.” (Galbraith, 331)

Yet, even if it was made as entertainment of the kind one can happily enjoy with popcorn and carbonated beverage, Sanjuro is not an empty film. It continues Yojimbo‘s exploration of the samurai film genre, while also playing around with the conventions of the historical samurai tradition. Like its predecessor, Sanjuro features stylised graphic violence, yet provides a message which questions its use and necessity. Similarly, in both stories the hero fights against corruption, a theme prevalent in Kurosawa’s films of the era.

For the home video availability of Sanjuro, see the DVD and blu-ray pages.

Please also note that our film for next month has changed, as instead of Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo, we will be watching Walter Hill’s 1996 film Last Man Standing, which stars Bruce Willis in a prohibition era remake of Yojimbo. For the full updated film club schedule (December’s film has also changed and will now be Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver), see here.

But that’s next month, and now we’ll concentrate on Sanjuro. What’s your take on the film, and how do you see it in relation to Yojimbo? To give one perspective, Stephen Prince calls Sanjuro a “much more modest” film which “does not extend the political, historical analysis of Yojimbo“, with Prince continuing by noting the bloodiness of the violence in the film and arguing that because of this bloodshed, the film’s “attempts to condemn such violence, by including a character who criticizes it, do not really work.” (233) What do you think?

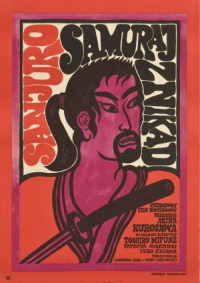

Image: Polish poster for Sanjuro, taken from moviepostersdb.com

I keep being surprised when I watch Sanjuro. Although it is, as Galbraith says, lightweight, not the masterpiece Yojimbo is, it’s a good film; within its genre, maybe even a great film. I’d also forgotten how laugh-out-loud funny it is in some places. I normally think of Yojimbo as more of a comedy than Sanjuro, maybe because the setup is more obviously, though darkly, comedic and absurd. It makes me wish that at some point in his career Kurosawa had made an out-and-out comedy. I bet it would be hilarious.

Maybe in the end what makes Sanjuro a less memorable film than Yojimbo is its conventionality. If it weren’t for the story elements, it could be a more or less typical chambara. It doesn’t have the mythic setting or quality of Yojimbo, which, even though it’s based on the economic and social conditions of the late Edo period, feels as if it’s set in a time and place of its own. The setting’s also more noticeably Japanese than Yojimbo‘s; this movie owes nothing (or at least little) to Westerns or Hollywood movies in general.

While I agree that the tone and milieu are different, and Mifune’s character is more mature and altruistic, I wouldn’t say that there’s little direct connection between Sanjuro and Yojimbo. In addition to the theme of corruption, albeit in this case more bureaucratic than economic, and hence not a critique of capitalism, there’s the ever-present theme of subterfuge and treachery in a good cause. Once again, Sanjuro engages in set-dressing and sleight-of-hand, including another scene in which he kills his opponents behind their backs and for awhile makes them believe that someone else did it. It also includes another set of hapless and hopelessly naive people whom he helps even though their stupidity endangers him and them alike.

The reappearance of Nakadai as a direct opponent is reminiscent of Clint Eastwood’s faceoffs against Lee Van Cleef in the sequels to A Fistful of Dollars. And, as mentioned, there are a lot of winks and nods to continuity in the music, the reference to the main character’s name (this time as a thirty-something camellia instead of a mulberry bush), and the closing shot, among others. Although it might have been unintentional, I’d include the use of doors, particularly shutting doors, instead of windows, as framing and punctuation devices as another of those winks and nods to continuity.

What sets the movie apart besides the crisp screenwriting and impeccable shot framing one expects in a Kurosawa movie is the role the aunt and chamberlain’s wife (whose name we never learn) plays. She, even more than Sanjuro, is the heart of the movie. At least twice she does unexpected things that actually improve their position. By showing mercy to the man they captured, they learn things they wouldn’t have if they’d killed him. (It’s surprising to me that they don’t also realize that if they treat him well, he might relent and give them information on his compatriots.) And by suggesting the use of a more peaceful signal than burning the house next door, she enables Sanjuro to trick the corrupt officials into helping him despite being held captive.

Because of this, I’d say it’s a standoff between her message of peace and the implicit message that the spectacular violence with which the movie is studded provides. It’s not just a matter of the movie including a character who condemns violence, or Sanjuro agreeing with her despite using violence. It’s a matter of the movie showing that refraining from violence can be wiser and can even improve the outcome. Ultimately, I believe the movie’s message is that while in an imperfect world violence is sometimes unavoidable — Nakadai’s character’s pride would not have allowed him to let Sanjuro leave without confronting him — non-violent solutions are better and should always be sought first.