Last month’s film club feature Sanjuro (1962) was based on a novel by Shugoro Yamamoto, and this month we continue in the same mode by moving onto Dodesukaden (1970), another work based on Yamamoto’s literary output, this time the short story collection A Town Without Seasons.

Last month’s film club feature Sanjuro (1962) was based on a novel by Shugoro Yamamoto, and this month we continue in the same mode by moving onto Dodesukaden (1970), another work based on Yamamoto’s literary output, this time the short story collection A Town Without Seasons.

Yamamoto’s influence on Kurosawa’s career in the 1960s does not in fact stop there. Between Sanjuro and Dodesukaden, Kurosawa had made Red Beard, again a Yamamoto adaptation, while also co-adapting another Yamamoto novel into Dora-heita, which would remain unfilmed until Kon Ichikawa dug up the script in the late 90s and filmed it for a release in 2000. In addition to the above four, also the first two posthumous Kurosawa films, Ame agaru (1999) and The Sea Is Watching (2002), were based on Yamamoto’s stories, further emphasizing the place that the author had in Kurosawa’s late career. It is therefore very unfortunate that Yamamoto’s literary output is practically unavailable in English, apart from the historical novel The Flower Mat (Red Beard, meanwhile, has been translated into French as Barberousse).

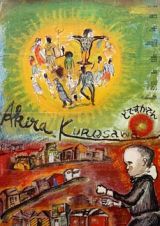

While we could then say that Kurosawa was on fairly familiar ground with the film’s source material, much of the rest of the film’s production was new and challenging. Dodesukaden was Kurosawa’s first film in colour, and his first without Toshiro Mifune in almost 20 years. The budget was significantly smaller than with his recent projects, and the two-month shooting schedule significantly shorter than had been the case with his preceding two-year project Red Beard.

There was also a sense of going back — perhaps somewhat untypical of Kurosawa. The film is often compared with The Lower Depths (see for instance Goodwin, 218), while the episodic narrative style employed is similar to that of Red Beard. After more than ten years of widescreen films, Kurosawa also returned to the “standard” aspect ratio, apparently both because of the intimacy of the shanty-town settings as well as because of the colours. (Galbraith, 478)

Dodesukaden was in fact Kurosawa’s first film in five years, the longest that he had taken between films in his career. Not that he hadn’t been busy, first preparing his first Hollywood film Runaway Train, and then taking over the Japanese part of the mammoth Tora! Tora! Tora! production. But both projects had fallen through, leaving the director with strained ties with both foreign and Japanese film studios.

This, combined with a rapid shift in the Japanese film industry towards cheap TV productions, drove Kurosawa, Kon Ichikawa, Masaki Kobayashi and Keisuke Kinoshita to form their own production company, Club of the Four Knights. Dodesukaden was their first production (after Dora-heita was deemed too expensive), and it was made with the intention of paving the way for a string of other high quality domestic cinema that would work to rejuvenate the Japanese film industry. This was not to happen, however. Dodesukaden failed at the box office, and was unable to make back the around $300,000 that it had cost to produce. As Galbraith suggests, this was especially difficult for Kurosawa, as the film had not only cost far less than his typical projects, but had also been finished “ahead of schedule and under budget” (485, emphasis Galbraith’s). Club of the Four Knights would never make another film as a production company.

Despite its poor performance at the box office, the film gained a cautiously positive initial response from critics both in Japan and abroad. (Galbraith, 485-486) As for later critics, the film has had both its defenders and attackers, and there appears to be very little critical consensus regarding its place in the Kurosawa canon, perhaps more so than with any other Kurosawa film. Joan Mellen in her essay on Dodesukaden for Richie’s The Films of Akira Kurosawa writes off the work as a “minor film that compares with Kurosawa’s great works only as a shadow resembles substance.” (Richie, 184) And as if there was nothing of interest to say about the film, the recent Criterion edition was also, untypically of Criterion’s Kurosawa DVDs, released without a commentary track. At the other end of the spectrum, David Desser in an essay for Post Script (vol. 20, fall 2000) sees Dodesukaden‘s place “at the top of the list of Kurosawa’s greatest films, virtually the equal of Ikiru, Seven Samurai, Yojimbo and High and Low, and in most ways superior to scholarly favourites like Rashomon and Throne of Blood.” (69) And then there is everything in between.

At least, then, there has been discussion. A fair amount of it, in fact, and for a relatively wide range of topics. As Kurosawa’s first colour film, the use of colour is much discussed. So is the type(s) of narration, and Kurosawa’s method of sewing together largely unconnected stories into a fairly coherent whole — some dismiss the film as one without a central story, while others praise it for its multiple layers. Similarly, Yoshimoto sees Dodesukaden as a very personal film, indeed almost autobiographical for Kurosawa, while others have insisted that they fail to see the Kurosawa that they know in the work.

One thing that critics do largely agree on, however, is that Dodesukaden marked a change in Kurosawa’s career. Whether it actually was the last film of an old era, the first of a new era, or a film between two distinct eras is debatable, but the consensus certainly is that Dodesukaden was and still is a flag pole, and a definite marker of change in Kurosawa’s career. Prince in fact goes as far as to say that it “looks like no previous Kurosawa film” and that it largely “lacks Kurosawa’s stylistic signatures” (251), suggesting a very fundamental change of direction in Kurosawa’s career as occuring with Dodesukaden.

What do you think? The forums are open.