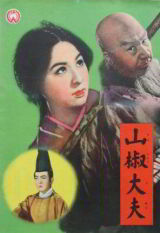

The October 2011 edition of our film club features yet another major classic of Japanese cinema, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff (Sanshoo dayuu, 1954). A historical film set in feudal Japan, it explores topics such as inequality, freedom, family, and women’s role in society. The film also explores Japan’s feudalism, both in historic and contemporary terms.

The October 2011 edition of our film club features yet another major classic of Japanese cinema, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff (Sanshoo dayuu, 1954). A historical film set in feudal Japan, it explores topics such as inequality, freedom, family, and women’s role in society. The film also explores Japan’s feudalism, both in historic and contemporary terms.

Although Sansho the Bailiff is much celebrated, my admittedly limited research suggests that it is one of those film classics that has actually generated surprisingly little substantial discussion. This, of course, is all the better for us. As for why Sansho the Bailiff appears to have remained less discussed than some of its contemporaries, I do not really know, but it may have to do with its emotional, as opposed to intellectual, content. Or, it may well also be the result of the film coming out at a time when the Japanese film industry was producing an astonishing number of other high quality works.

Mizoguchi himself had in the previous two years filmed The Life of Oharu (1952), Gion Music Festival (1953) and Ugetsu (1953), all films of high quality, and the last of which we will be visiting in two months’ time. But perhaps even more astonishing is the actual year when Sansho the Bailiff came out, for it was something of an annus mirabilis for Japanese cinema. November 3 1953 had seen the release of Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, and November 3 1954 would see the release of Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla. Between those two landmark films came out not only Sansho the Bailiff, but such other major works as Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, Keisuke Kinoshita’s 24 Eyes and Mikio Naruse’s Late Chrysanthemums. That’s quite something.

Sansho the Bailiff is available on DVD in both North America and Europe.

Our next month’s film club film is Kurosawa’s 1950 work Scandal. For availability, see Kurosawa DVDs.

The only substantive thing I’ve come across on Sansho the Bailiff is the very interesting commentary by Tony Rayns on the Masters of Cinema DVD. Its unfortunate that as a commentary its not footnoted, but its interesting that Rayns strongly implies that this film (along with Ugetsu Monogatari and Life of Oharu ) were at least partly motivated by jealousy at the success of Rashomon and his desire to put Kurosawa in his place. None of these films were seen as particularly good commercial prospects and in effect, Mizoguchi made his contemporary films as compensation. Rayns also indicates that there was a lot of studio interference with Sansho Dayu (sadly, it isn’t clear where the interference lay), which questions the assumption by many western critics that Mizoguchi could be considered an auteur on a level with Kurosawa and Ozu. it seems that only the latter two actually did have a creative free hand.

The other recent item I’ve read on Sansho Dayu was by David Thomson in ‘Have you seen….’ (I was browsing in a bookshop, I didn’t buy it), where he as usual compares Rashomon unfavorably to Sansho and Ugetsu Monogatari.