This March, our film club continues with the theme of nuclear bombing, as we watch Kurosawa’s penultimate directorial work, the 1991 film Rhapsody in August. The film follows four children who are spending a summer holidays with their grandmother in a small town near Nagasaki. During their stay, they learn about the atomic bomb which was dropped on Nagasaki and also killed their grandfather.

Preparations for Rhapsody in August (八月の狂詩曲 / Hachigatsu no rapusodī) began immediately after the release of Dreams (1990), a change of pace for the now 80-year-old Kurosawa who had for the past 25 years released a film only once every five years. The production was a departure from the past decades’ works also in that it was Kurosawa’s first fully Japanese funded film since the 1970 Dodesukaden, with Shochiku, Kurosawa Production Co and a group of investor companies behind the production.

The screenplay, adapted by Kurosawa alone, was based on the novel In the Stew (Nabe no naka) by Kiyoko Murata and reportedly written in just fifteen days. The film stars Sachiko Murase as a grandmother and bomb survivor Kane in what would be her last feature film appearance, crowning a 70-year acting career which started in theatre and saw Murase appear in close to a hundred films, as well as numerous works for television and radio. Before appearing in Kurosawa’s adaptation of In the Stew, Murata had already acted in the same role in a stage adaptation based on the same novel.

The other main roles are carried by child actors, all of whom have since continued working in the industry, and two of whom had already worked with Kurosawa on Dreams. In other roles, the American film star Richard Gere famously plays Kane’s half-American nephew.

Rhapsody in August was shot during 1990 and was released in Japan on May 25, 1991 to a polite but somewhat muted reception. The film was nevertheless nominated for altogether ten Japanese Academy Awards, winning four of them.

Reception abroad was similarly muted, with the United States an exception. At the time of its release, Rhapsody in August received more negative press in the United States than any other Kurosawa film had, as most American critics and journalists appeared to largely misunderstand the film’s themes and intentions. Rhapsody in August was attacked by them for being an anti-American film that simplified the complex historical and political situation which led to the atomic bombings, and was especially heavily criticised for a scene where Richard Gere’s character apologises to Kane. However, as Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto argues in his chapter on the film, these accusations are absolutely groundless and the result of a total and simplistic misreading of the film and the scene in question.

Rhapsody in August is in fact not all that interested in the atomic bombing itself or the events that led to it, and instead explores the rich and more interesting human element by asking how the bombings have in 45 years affected the society into which they were dropped. Instead of a political work, it is a film about memory, healing process and generational differences. In fact, as Stephen Prince writes, if the film does criticise something, it is the film’s middle generation who were born in the 1940s and witnessed Japan’s post-war economic boom. For them, the film has less sympathy than for the elderly or the young, portraying them largely as what Prince calls “greedy and shallow opportunists”. (318)

While Shohei Imamura’s Black Rain, which we watched last month, depicts the atomic bombing and its immediate reaction, Kurosawa therefore opts to approach the subject from a more detached position. In a 1991 interview quoted in James Goodwin’s essay “Akira Kurosawa and the Atomic Age” (published in Perspectives on Akira Kurosawa), Kurosawa in fact says about the atomic bombing:

It is absolutely unfilmable. That state of destruction and of such terrible human anguish does not belong to the realm of the presentable. … It is better to evoke and nurture the imagination; this is far more terrifying. I have not seen Imamura’s motion picture, but I think it is impossible to film such events. Things reach a point where the people who experienced the events cannot even speak of them. They are unspeakable.

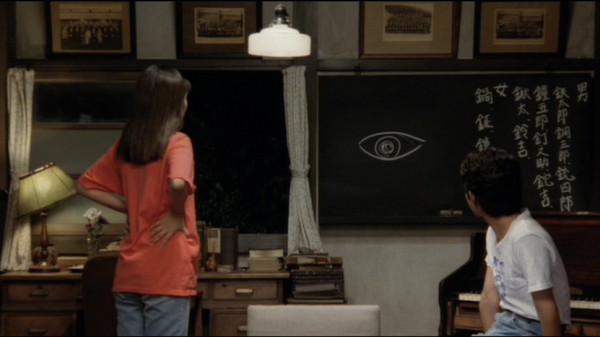

This impossibility of speaking about the bombing is effectively depicted in Rhapsody in August by Kane’s meeting with another elderly bomb survivor with whom she regularly meets to discuss the event. The two women sit in total silence.

Yet, by reminiscing about her siblings, Kane also ends up talking about the bomb and its effects on her family. This is significant, for in the end the film is not so much about the bomb as it is about a family that experienced it, and the three generations of individuals who each have a fairly different understanding of it.

For further background reading, the typical Kurosawa books found at the (recently updated) Kurosawa books section are recommended as always, as is Kurosawa’s contemporary discussion with Gabriel García Márquez that can be found for instance at Open Culture. For a biographical context, you can check out Part 11 of the Kurosawa biography which I have recently added to Akira Kurosawa info, while information about the film’s home video availability can be found at the DVD section.

Next month, we continue the nuclear theme with the Studio Ghibli film Grave of the Fireflies (1988). But that’s next month: the comments and forums are now open for your views on Rhapsody in August!

I had a free evening so managed to sit down and watch this again, I’ve had the DVD for some years and viewed the film at least a couple of times in the past.

Personally I like the film especially as it reminds me of my visit to Nagasaki during the scenes when the children tour the city.

Some scenes work a lot better than others for me, one example is the visit to the school yard, the first occasion when the children visit for the first time seems beautifully paced, moving and natural.

However the second visit, when the parents, children and Clark all arrive there at the same time to be surrounded firstly by the current schoolchildren at play and then by the ageing ex pupils that survived the bomb, seems too staged and contrived.

The generation gap theme reminded me a little of Tokyo Story with innocent children who lark about, materialistic and selfish adults and wise elders with many memories.

Both films explore the three generations but Kurosawa’s film gives the children a lot more voice.

I also saw similarities with Black Rain , exploring the lives of bomb survivors living a short distance away from the main city , people who were far enough away to witness the flash and the cloud rather than being hit by the full force but close enough to lose immediate family who were visiting the city and to suffer the effects of radiation.

Rhapsody being set at a later time explores memory of the ageing survivors set against the children discovering the past from their interaction with their grandmother and from the environment .

I particularly enjoy the performance of Sachiko Murase as the grandmother but Richard Gere always throws me a little he’s not around long enough for me to forget he’s Richard Gere and accept his character.

A favorite scene for me is where a friend visits Kane and they sit in silence together which we experience as the children see it and then find out more as Kane gives her explanation to the children.

The film certainly doesn’t come across as anti American to me and I’ve never thought Clark was apologising for the bomb itself. I always assumed he was apologising for not knowing about his aunt and not visiting previously, with these feelings being amplified by newly discovering his uncle was killed in the explosion. The feeling of guilt is then reversed as Kane learns the brother she didn’t visit in Hawaii has now died.