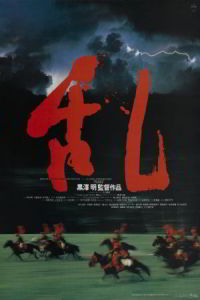

Ran, the film of the month for our Akira Kurosawa Online Film Club, holds a special place in Kurosawa’s oeuvre. It is the last of his great epics and a film that is often considered the culmination of his later period. Moreover, it is what the director himself at the time saw as rounding out his life’s work in cinema. And like any film with similarly high credentials, it is also known to divide both casual and dedicated audiences.

Ran, the film of the month for our Akira Kurosawa Online Film Club, holds a special place in Kurosawa’s oeuvre. It is the last of his great epics and a film that is often considered the culmination of his later period. Moreover, it is what the director himself at the time saw as rounding out his life’s work in cinema. And like any film with similarly high credentials, it is also known to divide both casual and dedicated audiences.

Ran was the result of a long creative process. Work on story of the 1985 film had started in the early 1970s, but Kurosawa’s difficulties in procuring financing for any film, let alone one of Ran‘s scale, forced him to put the project aside for years. So strong was the director’s urge to make the film however that he, just like with the preceding Kagemusha, practically created the film’s visuals on paper, drawing detailed and colourful illustrations of what was to be filmed, just so that something would remain of his vision in case funding would forever fail to materialise.

Fortunately, the story had a happier ending. As we discussed two months ago when we looked at Kagemusha, Kurosawa’s career received an unexpected new boost in the form of George Lucas. Thanks to the commercial and critical success of Kagemusha, Kurosawa was back on the map, and soon the French producer Serge Silberman, known for his work with Luis Buñuel, offered his help to fund Ran. And so, as with Kagemusha, the project moved forward with the help of overseas funding.

Similarities with Kagemusha do not end there. Ran is in fact often considered together with its immediate predecessor. There are a number of good reasons for doing so, not least because of Kurosawa’s often repeated comments which, perhaps half-seriously, describe Kagemusha as a commercially appealing dress rehearsal for Ran, the film that he had really wanted to make. The two films were inspired by the same historical period, with the historical Shingen Takeda, around whom Kagemusha revolves, and Motonari Mori, the model for Ran‘s protagonist Hidetora, dying only two years apart from one another. Thematically, both films look at the tragic destruction of a clan and family. The know-how and design choices made for Kagemusha also carry over to Ran. Much of the crew and some of the cast was retained, most notably Tatsuya Nakadai, who is once again cast in the leading role.

Yet, in some respects Ran and Kagemusha are almost polar opposites. Whereas Kagemusha follows the chaos of Japan’s Warring States period from a human level, Ran shifts the point-of-view high above to something that can justifiably be described a “heavenly” point of view. This difference has intrigued many commentators, even if Kurosawa himself thought that more had perhaps been read into the idea than he had intended:

“…some of the essential scenes of this film are based on my wondering how God and Buddha, if they actually exist, perceive this human life, this mankind stuck in the same absurd behavior patterns. … I wanted to suggest a larger viewpoint [than in Kagemusha] … I did not mean that I wanted to see through the eyes of a heavenly being.” (Cardullo 139-140)

Just like the narrative eye differs between the two films, also the viewpoints of the central characters are in stark contrast with each another. While the thief in Kagemusha constantly observes the external, trying to understand his surroundings in order to become another person, the attention of Hidetora in Ran is for the most part turned uncompromisingly and ultimately tragically inwards.

While Kagemusha was deeply rooted in its historical period and tried to comprehend the events leading to the destruction of an entire clan family, Ran, while up to a point still concerned with historical accuracy, is far more abstracted in its narration, as if the film were taking place in an enclosed world of its own. Ran‘s protagonist Hidetora is not intended to correspond with the historical character which inspired it, and similar abstraction is seen elsewhere, as for instance with the names of the warlord’s three sons Taro, Jiro and Saburo which literally stand for “first son”, “second son” and “third son” respectively (not an uncommon naming system in Japan). As Richie argues, the film is also more artificially structured than its predecessors, is loaded with metaphor and symbolism, and despite its overall gloominess utilises “near expressionism” in its visual presentation, which makes use of a vibrant colour palette that, as Sidney Lumet notes in his video notes on the Criterion DVD, is the exact opposite of what you might expect from a dark take on the King Lear story.

Ran‘s relationship with Shakespeare’s King Lear is of course another aspect that has drawn much interest. Ran was in fact not originally conceived as an adaptation of the King Lear story, and its origins lie instead in a well-known Japanese anecdote about Motonari Mori, who is said to have demonstrated to his sons the strength of unity by offering them three arrows: while each son could snap a single arrow, none of them could break a bundle of all three at once (see for instance Goodwin 196). While the legend is still taught today as a moral lesson and a good example of family loyalty, Kurosawa pondered what could have happened had the sons been more rebellious. It was only during the writing of the first draft that parallels between the story that he was crafting and that of Shakespeare’s play began to emerge, and Kurosawa decided to make further use of that connection. Kurosawa has in fact noted that by the time the film was finished, he was no longer always certain where Shakespeare ends and his own work begins (from Toho’s “It’s wonderful to create” series).

But there of course were also numerous differences. Perhaps most notably, as a clear departure from Shakespeare Kurosawa was interested in giving Hidetora a past, something that he noted Shakespeare’s protagonist lacking. This, Kurosawa reasoned, would make it easier for the audience to understand other characters’, especially so his sons’, relationship with the protagonist.

Together with the story, Ran in a sense also shares the world of theatre with King Lear. However, for Kurosawa the reference is not Shakespeare’s theatre tradition, but one closer to home. Just like with his earlier Shakespeare adaptation Throne of Blood, Kurosawa in Ran draws from Japanese theatre traditions, resulting in uncommonly expressive acting that deliberately goes against any standard notion of cinematic realism and further emphasises the abstract nature of the film. The end result is something that belongs in the realm of a legend or a myth, or something that is told not only to observe but to learn from. Far more than for instance with Kagemusha, the world of Ran is a stage.

Ran is not a happy film, and is in fact often considered Kurosawa’s bleakest work. As Prince (287-290) points out, the film is something of a trap for its characters, a world filled with cycles of violence where everyone is both a villain and a victim and where, unlike in Shakespeare’s world, almost no one is innocent or undeserving of the suffering imposed on them. The film’s final image is telling: the blind Tsurumaru wandering through the ruins and dropping his protective religious scroll as he almost stumbles down a steep stone wall. At the time of Ran‘s release Kurosawa was quoted saying: “All the technological progress of these last years has only taught human beings how to kill more of each other faster. It’s very difficult for me to retain a sanguine outlook on life under such circumstances.” (Prince 284) One wrong step, then, and it could all be over?

Ran was Kurosawa’s second and last film of the 1980s – a stark contrast to the pace in which he had been able to work earlier in his career. After Ran, it would be another five years until Kurosawa’s next movie, Dreams, which would mark the beginning of the director’s last creative burst that encompassed a set of three films released in four years.

What is your take on Ran? How does it hold up after repeated viewings? Some of our previous discussion on Ran can be found under the Ran tag.

The home video availability of the film is fairly good and for more information, see the Blu-ray and DVD sections. In December, we will follow Ran with something completely different, although contemporary. The film in question will be Juzo Itami’s hilarious Tampopo. The full film club schedule can be found at the film club page.

Great intro, Vili.

Its been a little while since I’ve last watched Ran, and I was thinking this time that for some reason this is one of AK’s films I tend to want to rematch certain scenes, but not the entire film. There are individual sections of Ran – such as the main battle scenes or the scene where Lady Kaede turns on her husband – which are among my very favourite scenes in all Kurosawa. But somehow I feel the entire film doesn’t always benefit from multiple viewings.

I think to a certain extent the film ‘is as it is’, it doesn’t have the multiple layers of other Kurosawa films, where every time you watch there is something new – a new possible interpretation, or just something so subtle that its easy to miss the first time watching. So I’m not sure I got more from watching Ran the second or third time, than from my first viewing, unlike, say, Seven Samurai or Yojimbo which seems to change for me every time I watch it. I don’t mean this as necessarily a criticism – I don’t think there is anything wrong with any work of art being so direct that there is little room for alternative interpretations – but I do think that it is perhaps a reflection of later Kurosawa being more of a true auteur, in the sense of pursuing one vision, than the earlier Kurosawa who seems to me to have been something of a sponge, taking on numerous ideas from his collaborators, leading to very rich and thematically complex films.

But I’ll watch it again to see if I’m wrong!