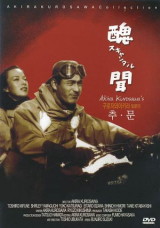

Our Akira Kurosawa film club‘s film of the month this November is Scandal (Sukyandaru or Shubun), Kurosawa’s 1950 film about the destructive powers of the tabloid press and the moral limits of free speech. It continues Kurosawa’s exploration of social challenges faced by post-war Japan, a topic he had already looked at in One Wonderful Sunday, Drunken Angel, The Quiet Duel and Stray Dog.

Our Akira Kurosawa film club‘s film of the month this November is Scandal (Sukyandaru or Shubun), Kurosawa’s 1950 film about the destructive powers of the tabloid press and the moral limits of free speech. It continues Kurosawa’s exploration of social challenges faced by post-war Japan, a topic he had already looked at in One Wonderful Sunday, Drunken Angel, The Quiet Duel and Stray Dog.

Scandal was released on 30 April 1950, with work on it having begun soon after the release of Stray Dog in October 1949. The exact timeline for its half-a-year gestation is however a little difficult to pinpoint from available sources. According to Galbraith, the film was “shot in late 1949 and completed in January 1950” (120), but in his discussion of the film Sorensen notes that a final draft was submitted to the occupation censors for pre-censorship as late as February 13, 1950. (205-206) Here, I would lean towards the timeline suggested by Sorensen’s remark, as the time between supposedly finishing the shoot in January and releasing the film in April would seem rather untypical of the way Kurosawa’s films were released at the time, with the films often being screened only days (or in the case of Rashomon, hours) after the work in the editing room had finished. In any case, unlike with his four previous post-war films, Kurosawa was able to make Scandal without much actual interference from censorship (Sorensen, 206).

The initial driving force behind Scandal was Kurosawa’s worry about the new freedoms of speech given to newspapers, which had increasingly begun to manifest in tabloid papers publishing scandalous articles in order to boost their sales. One such article titled “Who Stole X’s Virginity?” is in particular referred to in Kurosawa’s autobiography as an impetus for the development of Scandal. (177) And while Kurosawa does not mention it, Richie also adds that Kurosawa himself had personal experience of the tabloid treatment, having earlier been romantically linked to Hideko Takamine in the yellow press, the star of Horse (1941), and that this may well have also contributed to the birth of Scandal. (65)

While Scandal was Kurosawa’s first work not to suffer from any kind of direct censorship, its story, penned by Kurosawa together with Ryuzo Kikushima, was nevertheless compromised. Just like the spotlight in Drunken Angel had been stolen by Toshiro Mifune’s character and performance as the non-titular gangster, the main focus in Scandal begun to drift early on away from the original main characters played by Mifune and actress Yoshiko Yamaguchi, and more towards the lawyer character named Hiruta played by Takashi Shimura. This character, who in many ways resembles Sanada from Drunken Angel and Watanabe from Ikiru, turned the film into something quite different from what Kurosawa had originally envisioned. “From the moment this Hiruta appeared, the pen I was using to write the screenplay seemed almost bewitched. … As this happened, the character of Hiruta quite naturally took over the film and nudged the hero aside. Even as I observed what was happening and knew it was wrong, I could do nothing to stop it.” (Kurosawa, 178) Months after the film’s release, Kurosawa would suddenly realise that he had actually subconsciously based the character on a man whom he had met years earlier during a drunken night at a bar. (Kurosawa, 178-180) Talk about the dangers of heavy drinking.

As Kurosawa himself notes, Hiruta’s taking over the film has a rather detrimental force on the story, and it takes focus away from the film’s intended central theme. Kurosawa assesses that ultimately “Scandal proved to be as ineffectual a weapon against slander as a praying mantis against a hatchet. … Scandal did not prove strong enough.” (178) Shimura’s performance as Hiruta is nevertheless excellent, so much so that Richie considers it second only to Shimura’s work in Seven Samurai. (66)

Hiruta may in fact not be the only character in Scandal with a real-life counterpart. Actress Yoshiko Yamaguchi (also known as Yoshiko Otaka and Shirley Yamaguchi), who plays the role of a singer falsely accused of an affair with Mifune’s painter, was one of Japan’s most controversial and scandalous actresses of the time, and a big target of the tabloid media. As Ugetsu in a previous discussion on the film has noted, Yamaguchi’s “appearance in the film would have been quite ‘loaded’ symbolically for a contemporary audience”, and it is probable that Kurosawa cast her at least partly with this fact in mind. It has additionally sometimes been suggested that the painter character played by Toshiro Mifune could be seen as an alter ego of Kurosawa himself, who of course had studied painting and, as mentioned before, had himself been the target of tabloid stories.

Scandal is typically considered one of Kurosawa’s lesser works. In his chapter on the film, Yoshimoto writes that “despite the timeliness of its subject matter, Scandal is one of Kurosawa’s least convincing films. … Falling short of squarely dealing with the expansion of the media as a social problem, Scandal lapses into sentimental melodrama.” (Yoshimoto, 180) And indeed, Kurosawa’s portrayal of the media problem is rather one-sided. Richie, himself a newspaper man, observes that the journalists in the film are one-dimensional and too strongly and too lazily vilified, while the painter and the singer remain little more than empty props. In Richie’s view, only Hiruta ends up being an interesting character. (Richie, 66-68)

It must be noted, however, that focusing too much on how the film fails to properly tackle its media subject may be criticising it for something that it, in the end, was not necessarily aiming to do. As Richie puts it, by the end of the film we see that the scandalous posters of the alleged affair have now faded away, and everyone has moved on. “The suggestion is that things come and go, which is a singular way to end a protest film. On the other hand, perhaps the intention is ironic, perhaps Kurosawa wanted to indicate that, after all, all this fuss had been over very little. This would agree with the proposition that the true moral of the film has very little to do with hero or heroine — rather, that the true hero of the film is the lawyer. … The picture is a protest film all right but its protestations are not aimed at the world of the yellow press. They are aimed at the world itself, at this world which takes what is loved, which forces impossible decisions, which insists upon a choice among evils.” (69)

Whatever its goals, Scandal‘s debt to western film making has often been noted as another aspect which contributes to its relative failures. Galbraith argues that “the influence of Hollywood [on Scandal] is undeniable. For the first and only time, Kurosawa simply and obviously imitates rather than transcends his influences, trying to work through several major themes amid a patchwork of ideas. … The second part of Kurosawa’s film rather obviously apes Capra in general and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) in particular.” (120-121)

Just like Scandal has been accused of a lack of focus and original voice in the story department, it has also been criticised for its allegedly lacklustre style. Stephen Prince calls the imagery “for Kurosawa, amazingly pedestrian, but this may be in reaction to the formal energy of Stray Dog (1949), the film that preceded it and which Kurosawa felt was too full of ‘technique’.” (75) In his discussion, Prince links Scandal together with One Wonderful Sunday and The Quite Duel, calling them “necessary mediocrities, productions that enabled Kurosawa to relax between the rigors of the major works No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), Drunken Angel (1948), Stray Dog (1949) and Ikiru (1952)” (75), noting that in contrast to these latter mentioned, the three supposedly lesser works “have a placid surface that is marked by a general absence of radical formal experimentation.” (73)

Prince’s view is, however, not the only one. Richie for instance, while admitting the film’s failures, considers Scandal technically rather well made, praising in particular its editing and transitions. (68) Similarly, our own earlier discussion of the film — it was our film club feature for the first time in April 2010 — found the film to be more satisfying and layered than most critics have given it credit for. This has, in fact, been true of most of Kurosawa’s immediate post-war works, which we have typically found out to be more complex than the standard critical literature on Kurosawa’s works has assumed.

Scandal is, of course, both chronologically and thematically strongly linked to Kurosawa’s works of the late 1940s. James Goodwin draws a particular parallel to Drunken Angel and Stray Dog, arguing that while Scandal itself is not a gangster film, it still “extends the idea of criminality to include the ‘verbal gangsterism’ of gossip in the popular press”. (65) The film has in fact sometimes been seen as the end of Kurosawa’s second phase as a film maker. According to this view, Kurosawa’s next film Rashomon is a big departure from his wartime films and the post-war films of the late 1940s.

While this is true on many levels, reality is of course more nuanced and organic than this line of thinking would suggest. Scandal, in fact, already exhibits the first echoes of Rashomon, in as much as it centres around the unreliability of visual testimony, in this case a photograph. This topic of subjective truth is foregrounded from the very beginning in Scandal, with Aoye the painter working on a painting of Mount Kumotori that, according to the bystanding villagers, looks rather peculiar and very unlike any other depiction of that same mountain. In Rashomon, Kurosawa would take this questioning of subjective truth and testimony onto the next level, and in a sense also re-stage the courtroom scenes of Scandal, while also more directly asking questions about the relation between reality and (moving) picture. The jump from Scandal to Rashomon, which we will discuss in January, is therefore not necessarily quite as large as could at first be imagined.

For the availability of Scandal on home video, see my uide to Kurosawa on DVD. A full schedule of our film club can be found at the film club page, where you can also see that our film for December will be Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 masterpiece Ugetsu monogatari.

But November is all for Scandal. What are your views of the film and its position in the Kurosawa canon?

This is a great summary and overview Vili. My comments on this are slightly handicapped by a mechanical issue – a disk stuck in my dvd drive! But the film is still strong in my memory.

I’m still convinced AK’s intentions with the film were more broadly satirical about Japanese society and its thrall to American culture and mores than a simple attack on the yellow press. But, having watched since then a few older Capra films I have been wondering if some of the weaknesses of the films come from Kurosawa being a little too influenced by a type of film making that didn’t really suit him or the material? I’m thinking in particular of the courtroom scenes, which don’t really work that well for me.