February’s film club feature is Twenty-Four Eyes (Nijuushi no hitomi) by Keisuke Kinoshita (1912-1998), a director who is perhaps less well known in the west than his contemporaries like Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi or Naruse. Kinoshita is much better known in Japan however, so much so that director Masaki Kobayashi once called him the only film genius in Japan’s postwar era (quoted in Audie Bock’s Japanese Film Directors, p. 189), while Kurosawa in a 1960 interview with Donald Richie declared him second only to Mizoguchi (Cardullo, p. 7). Known for being famously prolific, Kinoshita directed his first feature in 1943 (just like Kurosawa), and for the next two decades released on average two films a year — an amazing pace considering the high quality of his work.

February’s film club feature is Twenty-Four Eyes (Nijuushi no hitomi) by Keisuke Kinoshita (1912-1998), a director who is perhaps less well known in the west than his contemporaries like Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi or Naruse. Kinoshita is much better known in Japan however, so much so that director Masaki Kobayashi once called him the only film genius in Japan’s postwar era (quoted in Audie Bock’s Japanese Film Directors, p. 189), while Kurosawa in a 1960 interview with Donald Richie declared him second only to Mizoguchi (Cardullo, p. 7). Known for being famously prolific, Kinoshita directed his first feature in 1943 (just like Kurosawa), and for the next two decades released on average two films a year — an amazing pace considering the high quality of his work.

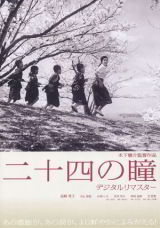

Twenty-Four Eyes, Kinoshita’s twenty-fourth film, was released in 1954 and is generally considered the director’s highest achievement. It was chosen the best film of the year by contemporary critics in the prestigious Kinema Junpo magazine poll, as well as winning the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film the following year. To put this into perspective, one should keep in mind that 1954 also saw the releases of such films as Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. The popularity of Twenty-Four Eyes continues today, with the film most recently having ranked 6th in Kinema Junpo’s 2009 anniversary list.

For our film club, Twenty-Four Eyes is a companion piece of sorts to Kurosawa’s 1946 No Regrets for Our Youth, which we watched in January and continue discussing. Although the two films are not exact contemporaries, they are thematically linked as both take us through Japan’s wartime years. Kinoshita’s film, having been made almost ten years after Kurosawa’s and the war, perhaps benefits from the distance, but both films can be seen as engaging in the gargantuan task of rebuilding a national identity. Both films also feature a strong female lead, with the woman at the centre being an educated city girl who moves into a rural community and has to struggle to find her place. In Twenty-Four Eyes, the main role is played by Hideko Takemine, who passed away only a month ago, on December 28, 2010.

As mentioned earlier, Kurosawa had much respect for Kinoshita, and it is perhaps surprising that in the small world of the Japanese film industry of the the time, the professional paths of the two crossed only a few times. Kinoshita’s 1948 film The Portrait (Shoozoo) was penned by Kurosawa, and the two would later work together also as part of the “Club of the Four Knights”, a production company that only ended up releasing Kurosawa’s Dodesukaden (1970). They also wrote Dora-heita together with the two other knights of the production company, Kon Ichikawa and Masaki Kobayashi. As with Kurosawa, the number of films directed by Kinoshita dropped in the 1970s as the Japanese film industry was struggling.

The general availability of Twenty-Four Eyes is pretty good. For region 1 (North America) there is a Criterion edition DVD, while region 2 (Europe) can purchase a very decent (and slightly cheaper) Masters of Cinema release. I’m afraid though that I don’t know if there is any region 4 release for those of you in Australia, New Zealand or Latin America.

In March, the film club will tackle Kurosawa’s 1947 film One Wonderful Sunday. For the full schedule, see the film club page.

I watched this for the first time over the weekend. A very interesting film and a great contrast to No Regrets for our Youth. As usual, I try to avoid reading up on a film before I watch it, so I’m only just catching up on some reading now. Richie doesn’t have much to say about it, although he clearly liked it as he defends it against claims that it is too sentimental.

As so often, I find Mellen has written some of the most interesting things about it, and I agree with her assessment, that basically it is half a great film. To be specific, the first half is wonderful. Its a sensitive, beautifully acted account that feels ‘real’ about what it was like in the 1930’s, as things gradually froze over, and militarism took hold. But the film is also quite obviously intended much more of a feel-good film than No Regrets. Unfortunately, this leads to the second half, in which it badly loses its focus and becomes a bit of a weep-fest with some quite facile politics.