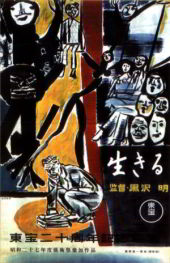

The May 2012 edition of our Akira Kurosawa Online Film Club features Ikiru, one of Kurosawa’s best known and most loved works, and the signature film of Kurosawa regular Takashi Shimura who plays the leading role.

The May 2012 edition of our Akira Kurosawa Online Film Club features Ikiru, one of Kurosawa’s best known and most loved works, and the signature film of Kurosawa regular Takashi Shimura who plays the leading role.

In Ikiru, Kurosawa returns to a setup and theme similar to one that he had explored only a few years earlier in two back-to-back films, Drunken Angel (1948) and The Quiet Duel (1949), while the 1950 work Scandal also featured difficult-to-cure disease as a prime motivator of character action. As in those films, the events of Ikiru are fuelled by the protagonist’s struggle with a life-threatening disease, although when compared with the earlier works, the results of Watanabe’s actions are more positive and less personal. Of these early medical dramas (if I am allowed a very lose definition of the term), Ikiru is arguably the most successful, and it was also Kurosawa’s last such film until he returned to the theme of physical disease in the 1965 work Red Beard.

Much praise has been lavished on Ikiru. Prince sees the film as nothing less than being “among Kurosawa’s most radical experiments with form and among his most searching inquiries into the nature and morality of human feeling, particularly in relation to its structuring by the cinematic image.” (100) He goes on to discuss Kurosawa’s connection with Brecht’s plays and especially the playwright’s method of “complex seeing”, where “the viewpoint of a play would emerge from a multivoiced montage of theatrical elements — characters, gesture, dialogue, set design, projected films and titles — rather than be easily localized within any one of these elements”, a method which Prince identifies also in Kurosawa, and especially so in the cinematic structure of Ikiru.

This Brechtian “complex seeing” is evident in the film’s utilisation of multiple points of view, which on the most basic level is structurally accomplished by the film being divided into two fairly independent parts, the latter of which consists of an almost rashomonesque attempt of interpreting the sequence and moving force behind the now-deceased main character’s actions. This structure was suggested by Kurosawa’s co-writer Hideo Oguni, a by then well respected screenwriter whom Kurosawa had known from the beginning of his career, but with whom he formally collaborated in Ikiru for the first time. The two were joined by Shinobu Hashimoto who had already worked with Kurosawa on Rashomon, and Ikiru therefore marks the first time that Hashimoto, Kurosawa and Oguni wrote together, forming one of film history’s most talented screenwriting trios, who would go on to collaborate, with occasional additional helping hands, on all of Kurosawa’s films for the rest of the 1950s, with the exception of The Lower Depths, to which Hashimoto did not contribute.

The narrative structure of Ikiru is discussed in length by many, including Richie as well as Goodwin in his book Akira Kurosawa and Intertextual Cinema. And although Goodwin does not mention it in his book, a certain level of traditional intertextuality was present also in Ikiru as, having just previously finished his Dostoevsky adaptation with The Idiot, Kurosawa turned to Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich as a thematic starting point for Ikiru (Galbraith, 156). The link, however, remains purely thematic in the finished film.

Several critics have talked about the feminine characteristics of Ikiru. Yoshimoto argues that “Watanabe is is consistently feminized”, something that is “most conspicuously manifested in his muteness” and in the way that he associates with female characters, even himself becoming a “maternal character” in his mission to push forward the construction of the children’s park (201). Also the character of Toyo, Watanabe’s inspiration in finding a new meaning for his life, has received much attention. Catherine Russell goes as far as to call her the “only really interesting female character in Kurosawa’s entire cinema”.

Ikiru is of course also a post-war film, and western influences are to be seen almost everywhere in the work. Some of them are for the better and some for the worse, and they range from various forms of popular entertainment to the nature of the bureaucratic machine itself within which Watanabe works, and which he ends up fighting. It has also been suggested that Watanabe’s cancer is in fact a metaphor for the westernisation of Japan.

Joan Mellen has argued in The Waves at Genji’s Door that while Kurosawa’s film condemns the Americanization of Japan, it does not blame the occupiers. In Mellen’s view, the underlying message of the film is that if your life is empty and without purpose, it is only you who are to blame, as change has to come from an individual awakening and effort. (231-233) In this view, it is not the occupiers who are to be blamed for Japan’s allegedly blind adaptation of foreign influences, but the Japanese themselves.

When released, Ikiru was an enormous critical and commercial success, winning among other things the Kinema Junpo Award for the best film of the year as well as a silver bear in Berlin. It remains one of Kurosawa’s best known and most highly praised works, and the simple question that the work poses the viewer — you may exist, but do you live? — continues to resonate well with today’s audiences.

We last discussed the film in late 2008, when the following threads were created:

– Ikiru: A Painting

– Ikiru: Nippon Beer and Critique of Post-War Society

– Ikiru: The Remake

– Ikiru: The Seat of the Soul

– Ikiru: The Son

– Ikiru: The Yakuza Boss

– Ikiru: Tilted Wipes

– Ikiru: Trains

For the availability of Ikiru, I recommend my DVD guide.

Finally, I would like to remind you that in June, we will be watching Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, which not only concludes the Noriko trilogy of Ozu films, but also shares certain themes with Ikiru, most notably the difficulty of communication between parents and children. For the full schedule of our film club, see the film club page.

As an aside, and considering we’ve been discussing Ozu a lot recently here, I see that Roger Ebert in his regular listing of his top ten films in his vote for the Sight and Sound ‘Best film of all time’ poll, considers Tokyo Story and Ikiru as pretty much interchangeable. It is odd how these two such different films are considered such a pair (and for the record, I can’t make up my mind which one I prefer either, they are both competitors for my all time favourite film).