Detail from a painting for Kagemusha (1980). Kurosawa drew and painted extensive and detailed plans for his final films.

By the late 1970s, Kurosawa was finding it impossible to get productions financed. Yet, in a manner of speaking the director had not been totally absent from silver screens. His influence on younger filmmakers continued to grow, and the filmgoers of the 1970s witnessed the emergence of a group of American directors who had been paying especially close attention to Kurosawa’s work. These filmmakers had names like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas.

Of these, it was Lucas who had been most visibly enamoured with Kurosawa. So much so that when his enormously successful space opera Star Wars opened in 1977, the more observant audience members could see a number of thematic, stylistic and plot connections with Kurosawa’s work, and especially his 1958 film The Hidden Fortress.

Lucas himself was keen to meet his idol, and when he did so he was amazed to hear about Kurosawa’s problems securing financing for new projects. In 1977, Star Wars had amassed almost $200 million in the US box office alone, and the 34-year-old Lucas was looking at a $30 million budget for his planned sequel. And here was a true legend of cinema still keen to create, but unable to do so only because no one was willing to back his considerably less expensive projects.

Of his planned films, Kurosawa had been working especially hard on three projects. One was a Shakespearean story set in medieval Japan (later filmed as Ran), another a project based on Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death (which remains unfilmed), and the third an original screenplay titled Kagemusha (“shadow warrior”). All three were period films since Kurosawa considered it impossible to find funding for stories depicting contemporary Japan.

Of the three projects, it was the Kagemusha script that Kurosawa considered the most commercially viable, and during the late 70s he had already been in talks about it with his old film studio Toho. The story certainly seemed interesting: very loosely based on historical characters and events from 16th century Japan, the epic film follows the story of a low-class criminal who, due to his uncanny resemblance to a dying old warlord, is taught to impersonate the warlord in order to maintain the illusion of the warlord’s continued leadership of the clan, and to keep both internal and external threats at bay for as long as possible. Yet, although Toho had initially showed interest, they had decided to pass due to the film’s estimated budget of $5.5 million, more than five times the cost of an average Japanese film at the time.

George Lucas, however, was in a position very different from Kurosawa’s. Lucas owned the rights to the Star Wars franchise, effectively giving him unprecedented negotiating power over film studios keen to distribute the film’s sequel. Following a meeting in July 1978 between Kurosawa and Lucas, it was decided that Lucas would help to secure funding for Kagemusha.

Lucas’s battle plan was elegant in its directness. 20th Century Fox, with whom Kurosawa had had his major falling out during the production of Tora! Tora! Tora!, was also the film studio responsible for distributing the first Star Wars film, and they were very much looking to work on the sequel as well. Together with Alan Ladd Jr (later founder of The Ladd Company) at Fox, Lucas negotiated a deal whereby Fox would co-finance Kagemusha in exchange for the foreign rights. From Fox’s point of view of course, it was an investment on Star Wars, more than anything else. Lucas was also able to attach his friend, film director Francis Ford Coppola to the production, and this calibre of foreign backing was enough to bring Toho back to the project. The Japanese company ultimately ended up spending around $6 million on the film, whose total cost climbed to around $10 million, or about twice the original estimate. The deal was finally announced on December 20, 1978.

And so, in the summer of 1979, Kurosawa was back behind the camera, thanks to the same film studio that a decade earlier had fired him from the set of Tora! Tora! Tora! and suggested that he suffered from mental instability, contributing in no small part to Kurosawa’s difficulties during the next ten years. Energised by the financial backing as well as the enormously positive public reaction to the news of a new Kurosawa film, the director set out to deliver his comeback. Yet, if Toho and 20th Century Fox had been hoping for a smooth production, they would soon be disappointed.

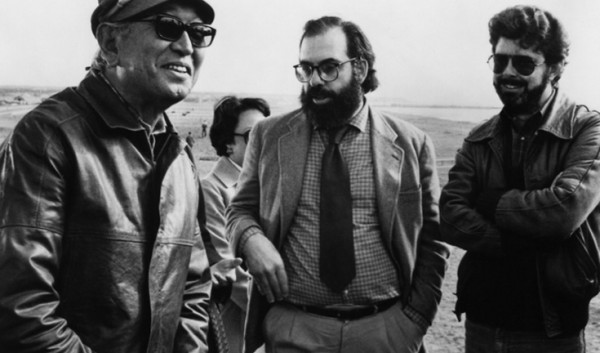

Kurosawa on the set of Kagemusha (1980) together with the film’s executive producers Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas

Kagemusha’s lead role, which in fact mandates a single actor to play two roles, had been written specifically with the popular Japanese comic actor Shintaro Katsu in mind, and Kurosawa had been able to secure him for the role. Yet, the personalities of the two men did not mix well and after an already troublesome pre-production period, Katsu ended up leaving the film set on the very first day of shooting. Accounts differ over whether he resigned or was fired, but the outcome was the same: the film that Kurosawa had just started to shoot was now without its leading man. Fortunately, Kurosawa’s name and connections were still valuable enough to deal with emergencies of this scale, and Tatsuya Nakadai who had previously had major roles in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, Sanjuro and High and Low, was soon attached to take over the lead role. This would affect the shooting schedule, but at least the crisis was averted.

Katsu’s departure would not be the end of production difficulties, however. While the departed leading actor was trying to drum up negative press coverage to get back at Kurosawa, the production also had to face a number of other challenges, including a nearby bomb scare, Nakadai being hospitalised after falling off his horse, a typhoon sweeping through the film’s Hokkaido set, the challenges of shooting a period picture in modern Japan littered with power lines and telephone wires, as well as the health-related resignation of legendary cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, who had earlier worked on Rashomon and Yojimbo. Miyagawa, who remained on board as a consultant, was replaced by the young Shōji Ueda and an earlier Kurosawa regular Takao Saitō, both of who would continue to work with Kurosawa until the end of his career.

Another change of key personnel happened in post-production when Kurosawa fell out with composer Masaru Satō. Despite having successfully worked on ten of Kurosawa’s previous films, from Seven Samurai to Red Beard, Satō decided to walk out following Kurosawa’s insistence on controlling the scoring process. Satō was quickly replaced by Shinichirō Ikebe, who had previously scored just four films.

Nakadai, Miyagawa, Saitō and Satō were not the only familiar faces on the Kagemusha set. A number of Kurosawa’s regular actors including Takashi Shimura and Kamatari Fujiwara had roles in the film, while Kurosawa’s old friend and collaborator Ishirō Honda, best known for his Godzilla films, worked as a close aide to Kurosawa, and would continue in this role until his death in 1993. Finally, and very importantly importantly, Kurosawa’s trusty right hand woman Teruyo Nogami was once again by his side, as she had been since Rashomon, and is credited as both the script supervisor and assistant producer.

Despite the well-oiled machinery that was provided by the Kurosawa regulars, the various setbacks and personnel changes resulted in the production falling behind the schedule, although perhaps by less than what Toho or 20th Century Fox had at times feared. Following a six month shoot and a frantic and energetic post-production period, Kagemusha finally opened on April 27, 1980, only two weeks after its originally intended opening date.

There was plenty of anxiety preceding the film’s release. Toho had ended up investing five to six times more money into Kagemusha than for an average production, and Kurosawa had his reputation very much on the line. Surely, if the film flopped it would mark the end of the now 70-year-old flimmaker’s career.

Luckily for everyone, the film did well. In fact, it turned out to be a big commercial hit both domestically and abroad, ending up not only profitable but in fact more than doubling the studios’ investment into it. The film was similarly a critical success, winning the coveted Golden Palm at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1980. Kurosawa, who had traditionally refused most promotional and press duties, spent much of the rest of the year in Europe and North America promoting the film, collecting awards and accolades and exhibiting the drawings that he had made in preparation for the film. In addition to its success in Cannes, the film won Best Film, Best Actor, Best Director, Best Art Direction, Best Film Score and the Readers’ Choice Award at the Mainichi Film Awards, as well as the Blue Ribbon and two BAFTAs, while also receiving nominations for the Best Foreign Language Golden Globe and Oscar.

Kurosawa had now succeeded in creating his comeback, and although he would not be returning to his pre-1965 rate of putting out a film every year, he was able to create again. Energised by the overwhelmingly positive public reception that his comeback had received and inspired by the memoir that his hero Jean Renoir had published in 1974, the usually very private Kurosawa set out to work on his own autobiography. The result, originally serialised in the Japanese magazine Shukan Yomiuri, was Something Like an Autobiography (Gama no abura), a partial and self-admittedly subjective look at the director’s life up until his international breakthrough with Rashomon.

Kurosawa’s next film project, Ran (“chaos”), would be an epic period film in the vein of Kagemusha, but this time largely based on William Shakespeare’s King Lear. As Japanese studios continued to feel apprehensive about the idea of producing another film that would rank among the most expensive ever made in Japan, international help was again needed, this time coming from Europe in the form of French producer Serge Silberman. Extensive preproduction work began in late 1982 but was halted in 1983 due to financing and other difficulties. While waiting for the production of Ran to continue, Kurosawa began working on Modern Noh (Gendai no noh), a documentary film documentary about Noh theatre. He would, however, leave the documentary unfinished once the production of Ran was able to continue again, with filming beginning in December 1983 and projected to last for more than a year.

Kurosawa on location filming Ran (1985), observing the controlled burning down of one of the film’s main sets.

In January 1985, towards the end of its projected production period, the filming of Ran was halted again as Kurosawa’s 64-year-old wife Yōko had fallen ill and the director wished to be by her bedside. The illness proved fatal, with Yōko passing away on the 1st of February. The mourning Kurosawa returned to the set to finish his film. Now a month behind schedule, Ran was not able to make its intended premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, and instead premiered at the Tokyo Film Festival on May 31, with a wide release following the next day. The film was a moderate financial success in Japan but a larger one abroad, and as he had done with Kagemusha, Kurosawa embarked on a trip to Europe and America, where he attended the film’s premieres in September and October.

Among other international awards, Ran was nominated for multiple American Academy Awards. Kurosawa lost in the Best Director category to Sydney Pollack for Out of Africa, which also bettered Kurosawa’s film in two other categories where it was nominated — best art direction (Yoshiro Muraki, Shinobu Muraki) and best cinematography (Takao Saito, Masaharu Ueda and Asakazu Nakai). But Ran‘s costume designer Emi Wada ended up picking up an Oscar for the Best Costume Design.

Kagemusha and Ran are generally considered among Kurosawa’s finest works and seen as remarkable examples of a director’s late career. However, the former film’s status remains somewhat overshadowed by the latter, not least because of Kurosawa himself at times suggesting that Kagemusha had functioned as something of a dress rehearsal for Ran, the film that he had really wished to make. After Ran‘s release, Kurosawa would also often point to it as the best film that he had ever made, a departure from his previous stock answer “my next one”.

The Life of Akira Kurosawa

- Part 1: Growing up (1910–1935)

- Part 2: Director in training (1935–1941)

- Part 3: Directorial debut, marriage and wartime works (1941–1945)

- Part 4: Son and immediate post-war works (1945–1950)

- Part 5: Daughter and international breakthrough (1950–1955)

- Part 6: Darker themes and move to widescreen (1955–1959)

- Part 7: New production company and the end of an era (1959–1965)

- Part 8: Unsuccessful Hollywood projects (1965–1969)

- Part 9: A difficult decade (1969–1978)

- Part 10: Comeback (1978–1986)

- Part 11: Final works and last years (1986-1998)

- Part 12: Death and posthumous works (1998-present)