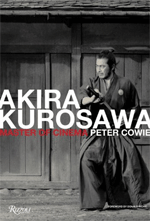

Peter Cowie’s new book Akira Kurosawa: Master of Cinema was published last week to roughly coincide with Kurosawa’s centenary on March 23. Being a coffee table book, it is first and foremost a fairly well put-together visual celebration of Kurosawa’s imagery, and only secondly a piece of argumentative film studies. This is perhaps somewhat disappointing, knowing Cowie’s reputation as a first class film critic.

Peter Cowie’s new book Akira Kurosawa: Master of Cinema was published last week to roughly coincide with Kurosawa’s centenary on March 23. Being a coffee table book, it is first and foremost a fairly well put-together visual celebration of Kurosawa’s imagery, and only secondly a piece of argumentative film studies. This is perhaps somewhat disappointing, knowing Cowie’s reputation as a first class film critic.

The book begins with a short foreword by Martin Scorsese, an introduction by Donald Richie, a tiny note from Kurosawa’s daughter, costume designer Kazuko Kurosawa, and finally an equally short preface by the author himself. These, like the rest of the book, are accompanied by various stills from Kurosawa’s movies, as well as posters, pictures of Kurosawa and his family, and drawings by both Kurosawa and his close aide Teruyo Nogami. The book also includes a number of script pages, with scribbles and drawings made while filming. It is this type of visual material that dominates the book, and one gets the feeling that the primary purpose of the included text is simply to fill up the spaces around the images and to arrange them thematically.

Chapter 1 (pages 36-51) is titled “The Man and His Formative Years” and it gives us some basic information about Kurosawa and his early works. Chapter 2 (pages 52-103), “Images of the Modern World”, discusses those Kurosawa films that take place in a contemporary setting, while chapter 3 (pages 104-185), titled “The Historical Imperative”, turns our attention to Kurosawa’s jidai-geki, or period pictures. These chapters, within which discussion progresses more or less chronologically, offer basically no new insights, instead repeating the typical anecdotes and bits of information familiar to anyone who has read a Kurosawa book or two. Of the pictures included in these chapters, the ones taken of Kurosawa with his family or the director at his summer retreat are perhaps the most interesting. Chapter 3 also includes a number of examples of Teruyo Nogami’s continuity sketches, while pages 100 and 101 present us a very nice side-to-side comparison of a scene from Madadayo and a storyboard painting that it was based on.

Chapter 4, “The Literary Connection” (pages 186-231), concentrates on Kurosawa’s most straightforward adaptations of western literature, namely the films The Idiot, The Lower Depths, Throne of Blood and Ran, with more than half of the chapter constituting of pictures from the last mentioned. This if followed by chapter 5 (pages 232-275) “Formalism and the Elements”, which is something of a hodgepodge of topics and is divided into subsections titled “water”, “air”, “fire”, “earth”, “painting”, “music”, “theatrical influences” and “color”. It is in these two chapters that one would expect Cowie to finally bring something of his own to the table, but unfortunately this is not the case. “The Literary Connection” chapter not only has very little substantial to say about Kurosawa’s literary adaptations, but like the list of films indicates doesn’t really bother with Kurosawa’s adaptations of Japanese works. Meanwhile, the sections in chapter 5 are nothing more than thinly veiled excuses to group certain types of pictures together, rather than prompting Cowie to provide substantial thoughts about Kurosawa’s relationship with the elements listed. However, as with the first three chapters, the images themselves are gorgeous and well selected.

The book concludes with the brief chapter 6 (276-284) titled “Riding into History”, which offers a few words about Kurosawa’s continuing influence. After the final chapter, we also get a very cursory filmography, a list of references, and a few acknowledgements.

All in all, Cowie’s book was clearly written with the coffee table book audience in mind. You can pick up the book, open it pretty much anywhere to read just a paragraph or two, and you are rewarded with a generic self-contained anecdote or thought. As the book was thus meant to be picked up and read randomly, it contains quite little real coherence or overall narration, preventing any real theorising or argumentation. As mentioned earlier, this is quite disappointing considering the calibre of the writer.

The pictures are, of course, nice to look at. So, if you feel the need to own a coffee table book which can function as a conversation starter, Akira Kurosawa: Master of Cinema is an excellent choice. For information about Kurosawa and his works, however, many better books exist.

Peter Cowie’s Akira Kurosawa: Master of Cinema is now available for purchase, including from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk and The Book Depository.

I just finished the book over the weekend – not difficult really, for such a hefty tome there isn’t a lot of text.

I broadly agree with Vili’s review. The book seems to be primarily aimed at the interested general reader. The selection and reproduction of the many stills, illustrations and reproductions is top class and makes the book worth its stiff price in my opinion – I know I’ll get many hours of pleasure leafing through it. They are very well chosen and there are quite a few I haven’t seen before.

The text is a bit of a mixed bag. I found it disappointing – but not because its bad, but because I get the impression that Peter Cowie has some very interesting things to say, he just doesn’t get around to saying them. While Vili thinks that it is designed for reading at random with the illustrations, I got the impression of a more comprehensive and serious book that had been edited down severely. To an extent, it almost seems like two books – the first half is a well written and lively (if not particularly novel or comprehensive) survey of Kurosawa’s life and works, while the second half reads far more like a deeper and more comprehensive treatise – but one in which most of the text has been removed. In fact, on more than one occasion I found myself flicking through the book after the end of a chapter, convinced that a page somewhere had been lost.

As Vili says, there is little here that would be new to anyone who’s read the main books on Kurosawa. What I did find interesting was Cowies comments on music – I found them very insightful and I’d love to read more of his views about that topic. He also makes a small number of interesting and insightful points – one that struck me as quite interesting is the notion that God is completely rejected in later Kurosawa films, implying that his earlier Buddhist tinged ideas were long in the past. He also implies (something that I’ve often had in the back of my mind), that the weaknesses in his late films may have been due to Kurosawas decision not to use collaborators in his later scripts. He does though, in my opinion incorrectly, ascribe Kurosawas willingness to work with script teams for much of his career to Japanese tradition, rather than a positive choice by AK. Cowie also rather annoyingly insists on drawing comparisons of the samurai films with westerns – I think this is highly misleading as it reinforces the old trope that Kurosawa was making westerns in Japanese costumes, something I don’t think many here would agree with (I certainly don’t). I suspect this may have been written as something of a sop to the books audience.