No Regrets for our Youth: That look on Yukies face

-

8 January 2011

10 January 2011

The scene certainly has a strong hint of the kind of melancholy and anxiety that you talk about, Ugetsu. Your interpretation of it is quite thought-provoking. My take is that Yukie’s reaction to the peasants has to do with their accepting her now, and in doing so silently admitting the mistake regarding their earlier reaction to Noge. Yukie ultimately seems kind of happy as the truck drives away from the camera. Noge has been absolved, not only by the intelligentsia, but also by the common people.

At the same time, the trucks at the end tend to remind me of wartime troop mobilisation. The war in the pacific may now have ended, but another kind of war is just about to begin, that of nation and identity building. It is into that war that Yukie is being taken to.

By the way, isn’t it “Mellen”, rather than “Mellon”?

10 January 2011

Vili

By the way, isn’t it “Mellen”, rather than “Mellon”?

Indeed it is! I realized my mistake a little while after posting, but the ‘edit’ function had gone – is it timed to go a certain time after posting?

My take is that Yukie’s reaction to the peasants has to do with their accepting her now, and in doing so silently admitting the mistake regarding their earlier reaction to Noge. Yukie ultimately seems kind of happy as the truck drives away from the camera. Noge has been absolved, not only by the intelligentsia, but also by the common people.

Interesting – I hadn’t thought of it that way – I’d forgotten completely to look at it from the perspective of the peasants and their presumed guilt (this does remind me of Martinez’s arguments about Rashomon being really about Japanese guilt). But what struck me about the reaction of the peasants was that they seemed in awe of Yukie. They didn’t greet her the way you would expect them to greet a fellow peasant.

Of course, one problem we have is interpreting Setsuko Hara’s interesting facial expressions! She was one of the best ever I think at indicating deeper emotions underneath superficial smiles or frowns. I think its Mellen who makes the comment that there is something rather ironic at how good Hara was at playing both ‘sides’ of the post-war Japanese woman – Kurosawa’s dynamic self-affirming heroine, and Ozu’s calmly accepting ‘proper’ Japanese lady. I should look again more closely at the end to this film, but I didn’t get the impression of genuine happiness in her smile and reaction.

At the same time, the trucks at the end tend to remind me of wartime troop mobilisation. The war in the pacific may now have ended, but another kind of war is just about to begin, that of nation and identity building. It is into that war that Yukie is being taken to.

Very true – there is something vaguely militaristic about that scene, although it may have been unavoidable given the context. Some films of the period – such as Mizoguchi’s Lady of Musashino have endings that are a little like that – in the case of ‘Musashino’, it is rather nastily didactic, as we are lectured on how beauty must be sacrificed in favour of the new, industrial Japan. The Yoshida Doctrine, which implicitly advocated a military style economic policy was, I think, only adopted some years after ‘No Regrets’ was made, but presumably some were advocating this approach at the time.

10 January 2011

Ugetsu: I realized my mistake a little while after posting, but the ‘edit’ function had gone – is it timed to go a certain time after posting?

Yes, there is a 60 minute window for corrections.

Ugetsu: But what struck me about the reaction of the peasants was that they seemed in awe of Yukie. They didn’t greet her the way you would expect them to greet a fellow peasant.

What you interpret as awe, I see more as slight embarrassment. I assume that their smiling and bowing intends to communicate to her that they are sorry, and that they would like her to become a part of their community.

Ugetsu: one problem we have is interpreting Setsuko Hara’s interesting facial expressions!

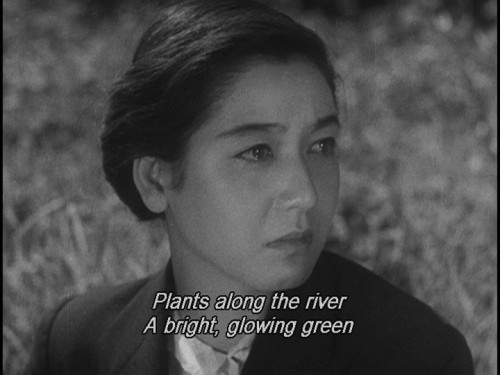

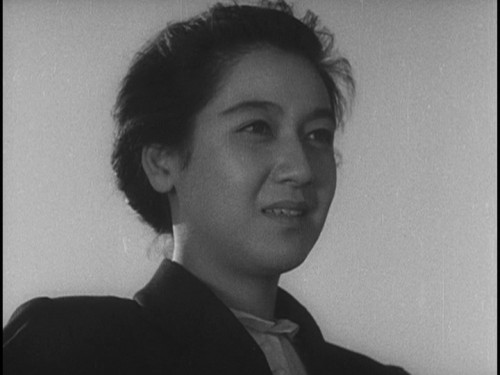

True, those are tricky sometimes! Here are some screenshots from the very last scene.

1. Nostalgically watching the students go by, singing their song about nature — a scene which seems to intentionally mirror the scenes early on in the film when students’ songs were all political (once again contrasting “empty” art and art with reason?).

2. Having boarded the truck and seen the peasants smile and bow at her. Seemingly a little confused.

3. Continuation of the above, her mouth transforms into a smile.

4. The truck is now going away, the final shot. She seems happy to me. (This picture is a little cropped, as I didn’t want to worsen the quality too much).

But I’ll rewind a little, if I may.

It is actually interesting to look at the last seven minute part of the film as a whole, and see how it wraps things up. A title card first rather dramatically announces that a “day of judgement” has arrived, with the war lost “but freedom … restored”. We are then taken to the university, and shown through Yagihara’s speech how the intelligentsia now praises the late Noge for his actions.

Always eager to subtly break the fourth wall, Kurosawa has Yagihara state that “there was a time when Noge sat right over there where you gentlemen are now sitting” while pointing at, well, you:

So, when Yagihara continues with the following words, there should be no doubt that the film is directly addressing its own audience: “I hope and expect that many, many more men like Noge will arise from your ranks”.

And in case you were doubting, this is one of the reaction shots to Yagihara’s speech:

Could well be a university auditorium, yes. But could also be a shot from inside a cinema. The film’s audience is now watching itself.

With Noge now absolved by the academics, the scene moves to Yukie’s mother and Yukie. The idea of things returning to normal after a period of ten-year-abnormality is mentioned by the mother — the idea that the war has been a simple misstep. But despite her wishes, something actually has changed: Yukie has changed.

Sitting by the piano where she sat when Noge confronted her about not doing anything worthwhile, Yukie explains her decision to continue working with the peasants even after she has made Noge’s parents understand Noge’s actions. The gist of it is that she feels that she can still help those whose lives are brutally hard — especially women. She then repeats Noge’s motto which is also more or less the title of the film, adding that that’s the source of her happiness, and in so doing suggesting that it is still first and foremost for the memory of Noge that she is doing all these things.

We then cut to the countryside, Yukie staring at water. The singing students walk by who, as I mentioned earlier, connect the end of the film to the beginning. This is followed by Yukie getting onto the truck. The scene on the truck mirrors the earlier scene with the academics. Whereas we needed a great number of words from Yagihara to praise Noge and formally communicate his absolution from the part of the academic world, all we need from the peasants are those few nods and smiles. With their acceptance, Noge is now fully freed from any ill thoughts, and Yukie, as I mentioned, seems to be smiling as she is taken away from us, into a new war of sorts.

It is indeed quite a brilliant last seven minutes.

11 January 2011

I wish I could do those screenshots! They look great.

I’ll have to have another watch to clarify my thoughts, but just a few observations:

Your comments about the final ‘speech’ by the prof is very good – I’m sure thats exactly how it was intended. It hadn’t occurred to me that he was pointing directly at us (the audience). Although I’m a little surprised that got past the American censors – wasn’t Noge based on an individual who had been executed for helping the Soviets? Sounds like that could have been interpreted as a call to arms for the Reds!

My interpretation of Yukies transformation is somewhat different from yours. I think that earlier on, the ‘flower arranging’ scene is crucial. Yukie is a born rebel, but she hasn’t a cause. But for me, what is crucial is that she didn’t actually follow Noge. She never attempted to contact his associates or help in his office. She found her own way. Initially, through the ‘traditional’ Japanese way of her helping her in-laws. Later, by becoming a community organiser, which was something very different from the much more clandestine and potentially violent path of Noge. It seems to me that AK was quite deliberately setting out the four ways of opposing evil:

1. Classic intellectual liberalism (Japanese style), as represented by the Professor.

2. Youthful rebellion, followed by a reluctant conformity, but ultimately working to improve the system from within, as represented by Yagihara.

3. Outright rebellion and subversion, by Noge.

4. Rejecting the ‘system’ (in this case, the family itself), but working within the wider community (if necessary, as an ‘outsider’) to improve it, the road as ultimately taken by Yukie.

I think the film is quite deliberately non-didactic as to which is best, as none of the characters are condemned or shown to have failed outright. But what is clear is that as individuals, all four ‘succeeded’ by doing what they felt was right in the circumstances, despite the apparent doubts all four characters show at various times. Even Yagihara, despite his apparent treachery and his shame at having become a prosecutor, did the right thing by his mother. To have become a rebel would have condemned his mother to a life of poverty, hardly a worthy thing to do.

So, in classic Kurosawa style, you ‘succeed’ only by reaffirming the self, and finding your own path to meaning. But it is impossible to ‘succeed’ in this way, without sometimes paying a heavy emotional price.

11 January 2011

Ugetsu: I wish I could do those screenshots!

If I remember correctly, your computer drive can read DVDs from any region. If so, install VLC media player, which can play pretty much anything you throw at it. While playing the film, you can make screenshots very easily through Video > Snapshot (or that’s how it is in the Windows version). In the preferences, you can also set the folder that the program uses for screenshots.

You should also have the ability to upload files to this website. If you have no “Upload” link next to the “Discussion” link in the header of this website, let me know. Not everyone has it, as I’ve given it mainly to those who have asked (and for security reasons I will be giving it only to those members who have been around for a while). I admit that it’s not the most convenient way of uploading stuff, but let me know if you use it what could be done to make it better.

While the website can handle pictures of any size, the forums currently resize pictures larger than 500 pixels in width to fit onto the page. Depending on your browser, this can lead to poor quality, so it’s recommended to resize the pictures manually before uploading (this also saves space and my bandwidth). The quickest way to resize pictures is probably to use IrfanView, which is a really fast, powerful and easy to use image viewer. It’s not a real editing software, but does the basic stuff really well.

I hope this helps!

Ugetsu: Although I’m a little surprised that got past the American censors – wasn’t Noge based on an individual who had been executed for helping the Soviets? Sounds like that could have been interpreted as a call to arms for the Reds!

Indeed. But perhaps at this point in time in what was still a pre-McCarthy era it was still seen as Noge/Ozaki having helped the Allies, and not just the Soviets?

Ugetsu: My interpretation of Yukies transformation is somewhat different from yours.

Indeed, we seem to differ quite a bit here!

You write that Yukie “never attempted to contact [Noge’s] associates or help in his office”. Do you think that she could have done that even if she had wanted to?

Ugetsu: It seems to me that AK was quite deliberately setting out the four ways of opposing evil

That’s a very good point! However, I think that Yukie’s work within the community only really begins after the war, once Noge’s family has been accepted again by the other peasants. To me, up until the end of the war she just seems to be working for Noge’s memory and reputation, and is therefore not really part of those opposing the wartime powers. Or I just can’t really see it in any other way.

Ugetsu: as individuals, all four ‘succeeded’ by doing what they felt was right in the circumstances … So, in classic Kurosawa style, you ‘succeed’ only by reaffirming the self, and finding your own path to meaning. But it is impossible to ‘succeed’ in this way, without sometimes paying a heavy emotional price.

Thanks for this! I am finally beginning to see why everyone — including Kurosawa — is talking about the film being about the “self”. I think I’ve been too fixated on Yukie, who I feel is anything but herself until the very end of the film. When she steps onto that truck, that could be Yukie finally doing her own thing. Everything before that, I feel she is pretty much doing for Noge.

11 January 2011

Thanks for the links, Vili! I’ll have a go at that, its so much more interesting when a comment has screenshots (I just hope I have the patience to work it out).

You write that Yukie “never attempted to contact [Noge’s] associates or help in his office”. Do you think that she could have done that even if she had wanted to?

Probably not – although what struck me is how little interest she showed in what they were doing and how content she was to play the ‘good wife’ before and after his death. It seemed to be signalling for me that she had already made up her mind that such active rebellion was not for her – but she was happy to stay on the path of supporting her husband in what he was doing until she had discovered her own path. In other words, she was doing what she felt intellectually what was right, while patiently waiting to find what felt emotionally right for her. It is in the fields, with her in-laws, that she found her niche in life, so to speak.

15 January 2011

Ugetsu: It seemed to be signalling for me that she had already made up her mind that such active rebellion was not for her – but she was happy to stay on the path of supporting her husband in what he was doing until she had discovered her own path. In other words, she was doing what she felt intellectually what was right, while patiently waiting to find what felt emotionally right for her. It is in the fields, with her in-laws, that she found her niche in life, so to speak.

This sounds perfectly plausible, although I see it in almost completely opposite terms. To me it seems like she is following her emotions when helping Noge’s parents. The intellectual decision is to go back to live with the peasants after the war has ended and Noge’s name cleared.

But maybe we are still saying the same thing, and just defining an “intellectual” or “emotional” act differently in this case?

15 January 2011

Vili

This sounds perfectly plausible, although I see it in almost completely opposite terms. To me it seems like she is following her emotions when helping Noge’s parents. The intellectual decision is to go back to live with the peasants after the war has ended and Noge’s name cleared.

Yes, I think you are quite right – she did seem to decide to go to Noges parents as a sort of instinctive act. It reminds me a little of Noriko’s faithfulness to her husbands memory and her in-laws in Tokyo Story. So it was her decision to return later that was a more conscious, intellectual act – she came to her decision only after she joined his parents.

10 April 2011

It’s a good thing I haven’t read any analysis of Kurosawa’s movies other than Richie’s fairly superficial one because from what I’ve read of them here, I often think they’re way off base. Here, I disagree with all of them, most vehemently with Yoshimoto. I do not think Yukie is being self-sacrificing in returning to the village. This is the work that she can throw herself into that she and Noge spoke of. She’s found community and acceptance, she’s forged a relationship with her husband’s family, and she’s needed there. She’s not needed in Kyoto, and if she returned, she’d be turning her back on finding her own self-worth and making a difference, substituting her mother’s desires for her own, and returning to the same empty life she rejected when she left for Tokyo.

To me, she looks content and determined. I interpret the look on her face when the peasants bow to her as humility, possibly uncertainty, not confusion. She knows what they mean by it; she’s signaling that she doesn’t think what she’s done is such a big deal.

I’m not sure I agree that Itokawa tried to achieve reform from the inside. I think instead he became a collaborator who used his position to ameliorate its effects on people who were his friends. He wasn’t willing to rock the boat, nor is there any evidence that he tried to change internal policy. That, I think, is why Yukie refused to let him visit Noge’s grave. While Noge’s decision not to drop out of school saved his mother from poverty — I’m not convinced that the prosecutor’s office was his only option once he graduated — the only difference between him and Noge was that Noge’s decision didn’t condemn his parents to more economic deprivation than they already experienced.

While Kurosawa shows that each character has reasons for her or his approach, I think Yukie’s is implicitly endorsed above the others. It’s not clear from the movie whether Noge actually accomplished anything during his lifetime for standing up for his beliefs other than being arrested and executed; his exoneration comes after the war ends and people realize that Noge was right all along about Japanese militarism. As Noge predicted, the professor’s less activist approach didn’t accomplish anything for academic freedom and left him without employment or status for twelve years. (The movie says it’s been ten years, but that’s wrong; he lost his job in 1933 and the war ended and he was reinstated in 1945.) I’ve already discussed Itokawa’s approach.

It’s not clear to me that Yukie didn’t want to help Noge in his work given what she says to him about finding work that’s important. That sounded to me like a statement that she came to him because of his commitment to a cause that she sought to embrace herself. His keeping her out of it was to protect her; for all we know, if he’d been willing, she would have helped out — if not at the office, then by talking things over with him at home.

I think there was an emotional component both to her decision to stay with Noge’s parents and to return to the village, though the former was more purely emotional.

11 April 2011

Lawless

I’m not sure I agree that Itokawa tried to achieve reform from the inside. I think instead he became a collaborator who used his position to ameliorate its effects on people who were his friends. He wasn’t willing to rock the boat, nor is there any evidence that he tried to change internal policy. That, I think, is why Yukie refused to let him visit Noge’s grave. While Noge’s decision not to drop out of school saved his mother from poverty — I’m not convinced that the prosecutor’s office was his only option once he graduated — the only difference between him and Noge was that Noge’s decision didn’t condemn his parents to more economic deprivation than they already experienced.

I think whats interesting about Itokawa as a character is I would imagine he is the one most audience members would have had most empathy. Very few people would have been as rebellious as Noge or in a position to maintain a sort of Olympian disdain for the government as the Professor. But many people who didn’t support militarism would have gone into the system somehow, and justified their decision in one way or another. So I think that for Kurosawa to have utterly condemned Itokawa would have been a step too far for the audience. I think he was showing the uselessness of his actions, while also allowing a certain amount of sympathy for his situation.

11 April 2011

Ugetsu – True, Itokawa was more of an Everyman. Most people don’t stick their necks out the way Noge and the professor did. The movie does, however, seem designed to glorify the heroic and exceptional and to encourage people to emulate them.

I wasn’t sure where to mention this, but I wonder if the occupation authorities or, more likely, Toho’s labor union had a hand in Yukie’s refusing to let Itokawa visit Noge’s grave. That seemed out of character for Kurosawa, who seemed to espouse a more conciliatory approach, and I wonder if that was the way the script was originally written or if it was changed.

Yukie took offense at Itokawa’s claim that Noge took the wrong path, but isn’t that itself a denial of Itoakawa’s right to his own opinion and thus at odds with the theme of freedom espoused here? It’s clear that Itokawa wanted to visit the grave out of respect to the memory of a friend irrespective of their opinions and political leanings. It seems to me that should have been encouraged. But maybe that was too inflammatory a topic, seeing how fraught the issue of visiting memorials to the war dead has been even more recently.

12 April 2011

Lawless

I wasn’t sure where to mention this, but I wonder if the occupation authorities or, more likely, Toho’s labor union had a hand in Yukie’s refusing to let Itokawa visit Noge’s grave. That seemed out of character for Kurosawa, who seemed to espouse a more conciliatory approach, and I wonder if that was the way the script was originally written or if it was changed.

Interesting question. I did find it odd when watching the film that she seemed to suddenly turn against Itokawa in quite an irrational manner – or at least inconsistent with her previous friendship to him. And the scene did seem a little unnecessary to me, it didn’t advance the story. I took it as indicating her newer, more radical politics (although it seems odd that this occurred well after Noges death, rather than when she was married to him). So yes, I do think its possible that this scene was a somewhat later addition (or possibly the remainder of a subplot that was partially removed).

14 April 2011

lawless: It’s not clear from the movie whether Noge actually accomplished anything during his lifetime for standing up for his beliefs other than being arrested and executed

Ugetsu: I think whats interesting about Itokawa as a character is I would imagine he is the one most audience members would have had most empathy.

This is very true. I wonder if this is why there were “no regrets for our youth” — if you were able to say that in 1946, you may not have stood up against the regime, but at least you were alive.

Ugetsu: I did find it odd when watching the film that she seemed to suddenly turn against Itokawa in quite an irrational manner – or at least inconsistent with her previous friendship to him. And the scene did seem a little unnecessary to me, it didn’t advance the story.

This scene is puzzling to me as well. But then again, most of the final act is.

The idea of the scene as being a leftover from an earlier draft sounds like an interesting theory. It would be great to be able to read the original screenplay(s).

16 April 2011

Vili – The scene between Yukie and Itokawa puzzles me; it’s the opposite of what I would expect from Kurosawa. In addition to the possibility that it was added, I wonder if the ending was changed. At any rate, it smacks of interference from Toho’s scenario committee. However, I can see its purpose as showing how the various parts of Japanese society, including the collaborators, tried to reconcile themselves afterward, and whether those who sacrificed much in opposition should or could ever forgive those who stood with the regime.

18 April 2011

Vili

This is very true. I wonder if this is why there were “no regrets for our youth” — if you were able to say that in 1946, you may not have stood up against the regime, but at least you were alive.

Funny thing – its a somewhat obvious question that hadn’t crossed my mind until you mentioned it. Is it a direct translation from the Japanese? Am I right in saying that the phrase became something of a catchphrase for radical youth in period immediately after the release of the film?

I wonder if its meaning is to say that compromise (in the way Itokawa compromised) will lead to regrets. Only Noge and Yukie could be said to have no regrets because they followed their consciences.

The idea of the scene as being a leftover from an earlier draft sounds like an interesting theory.

Off the top of my head, I think this is the only Kurosawa film which seems to have this somewhat unfinished tone. It does feel like there were maybe a few too many cooks involved in the script and that some hasty work was done to try to satisfy various plot strands that didn’t add up in the end.

19 April 2011

Ugetsu: Is it a direct translation from the Japanese?

I think so. Waga seishun ni kuinashi = “our youth for regret-without”. Although if one wants to give it an autobiographical read, “waga” could I think also stand for “my”, making it No Regrets for My Youth.

Ugetsu: Am I right in saying that the phrase became something of a catchphrase for radical youth in period immediately after the release of the film?

Indeed, that’s what we are told.

Ugetsu: I wonder if its meaning is to say that compromise (in the way Itokawa compromised) will lead to regrets. Only Noge and Yukie could be said to have no regrets because they followed their consciences.

It could be that as well. Although I don’t think that anyone is actually expressing any regrets in the film. Maybe the suggestion is that no one among the general population should have any regrets, as the evil done at the time of the war was done because of a handful of people at the top.

But then, the ending comes across so sad that I feel that if anyone should have regrets, it is probably Yukie.

19 April 2011

Vili

Maybe the suggestion is that no one among the general population should have any regrets, as the evil done at the time of the war was done because of a handful of people at the top.

I would have thought the Occupation authorities would have objected to the title if they thought that was the intention. I thought they were still very much in the mode of getting the Japanese people to see the error of their ways. It would, though, be an interesting contrast to Martinez’s theory that Rashomon was really all about guilt over the war.

I would have thought the meaning of the title was more along the lines that people who actively stood up in some way, either before, during, or immediately after the war (as most of the characters did to some extent), shouldn’t have regrets, even if it turned out bad for them. Better to stand up against evil and fail rather than do nothing.

I suppose another interpretation could be: ‘We all do impetuous and stupid things when we are young – so long as the intention was good, we should not regret anything.’

21 April 2011

I thought the title was somewhat ironic because it seemed to me that Noge, the originator of the phrase, harbored regrets about his parents; he just didn’t dwell on them. That might have been part of the reason why Yukie decided that going to see them and help them out was the right thing to do.

Otherwise, though, I took it to mean to live life to the full and commit yourself fully to what you believed in. In the end, Itokawa didn’t really believe in anything but survival, so while he may not have regrets — or he’s not shown having them — in some ways, having compromised or flipflopped his beliefs, he should be the most regretful of them all. Even Yukie’s father is shown to have regrets in the speech in which he rehabilitates Noge’s memory.

22 April 2011

Ugetsu: I would have thought the Occupation authorities would have objected to the title if they thought that was the intention. I thought they were still very much in the mode of getting the Japanese people to see the error of their ways.

I’m not so sure if this is true. My understanding is that the occupation government was not seeking to blame the Japanese population, but rather to deal with the real causes for the war and to get the rest back on the track and towards democratisation as fast as they could. Very little could come out of dwelling on the mistakes of the past. Hence, I would think that “no regrets” would actually have been an encouraged as an approach.

I’m not saying that this is necessarily the correct or only interpretation of the title, however. It could well be, as you suggest, primarily a reference to Noge. And if so, what lawless points out gives the title an interesting nuance.

Leave a comment

Log in or to post a comment!

Like a lot of people who have written about the film, I find the ending, in particular, that ambiguous look on Yukies face as she disappears into the distance to be fascinating.

Richie (p.40) says about it:

Yoshimoto (p.134) says:

Mellon (page 45) says:

I think Yoshimoto is closest to what it really represents. What I found striking in the final sequence is that while the peasants were obviously happy to realise who it was they’d picked up, they were also clearly in awe of her. She recognises this, and her face shows her ambiguous feelings about this. She may have decided to live with the peasants, but she will never be one of them. She will either be an outcast, or a leader. In this manner, I think Mellon has it wrong – while Yukie wants to live with ‘the people’, she can never transcend her history and her upbringing.

I find the ending to be in fact, one of Kurosawa’s most important, honest and disturbing. There is no optimism for the future, no easy ‘victory’ for the good guys, nor, for that matter, a fashionably nihilistic pessimism. Yukie has made her choice, but it is not an easy one and there is no guarantee it will be a happy one in the end. These are the same people who were vicious to her and her in-laws just a year or so before. Rather than the calm acceptance of Ozu, there is a life of turbulence ahead. And in the context of the time, I think Kurosawa was correctly identifying that the future for Japan would involve a very difficult road, and most pessimistically, even the ‘right’ choices, would not necessarily result in happiness or contentment, or even the sort of nobility of acceptance. He shows us the failure of the ‘establishment’, but also the failure of liberalism and radicalism. But the way of the ‘self’ (which I would imagine would have been seen in the context as the ‘American’ way), while the only option for many that would preserve self respect (and by implication, national self respect for Japan), was not the road to contentment or happiness.