Rashomon: the symbolism

-

6 May 2008

7 May 2008

Actually I’m always more interested in what people that havent been involved in cinematography have to say about certain directing choices.

Thats if they even found anything that stood out as interesting and worth mention.

I often think that some people over think the story and/or the directing too much.

Does any artist really put that much thought in everything they do, are not somethings if not most, just simply are what they are and nothing more.

This is not directed at you sanjuro, it really to all of us, including me.

Does the average viewer even get anything that we put into these movies, or do only a select few find deep meaning behind them?

Would not the vast majority of people, watch Rashomon (if they didnt fall asleep) find anything more then, that in the end– everyone is a lair–big deal, goodbye. (?)

Not sure what it was that got me off subject, must of being something sanjuro said, along with me battling if I’m really just trying to fit meaning into everything, just for the sake of it.

Anyways I have some stuff I like to discuss about the rain and something I’m glad sanjuro mentioned-the stream of water, something I largely ignored but still found it dancing around in my head, every time I see the movie.

I’ll have to get back to you on this, bed time has sneaked up on me and I dont feel I’m in the right frame of mind right now.

7 May 2008

As a response to Jeremy’s post, I think that trying to find out what people making the movie intended to communicate is one way of approaching a film, but I think that it is ultimately an exercise in the study of film history and film craft, rather than an examination of the work of art itself.

I personally don’t think that when looking at a piece of art you should be restricted by what you know or suppose was intended and what wasn’t. What I am far more interested in is how it all is ultimately experienced — by me, by you, by the original audience, by anyone. And this is not only because it is a fun exercise in itself, but because as a wanna-be-artist and something of a wanna-be-cognitive-scientist I want to know what happens to people when they are presented with this or that.

Moreover, I don’t think that any artist is ultimately totally conscious of what they are doing. Kurosawa himself repeatedly said that he did things in a certain way not because he thought it was the right way to do, but because he felt that it was. He also noted that if he could have just rationalised and said what he intended to communicate, he wouldn’t have needed to film it in the first place.

I am not saying that what Kurosawa and his crew intended is irrelevant, far from that. But what I am saying is that there are more than one way of experiencing and interpreting everything, and none of these is ultimately less valid than the other. They may serve different purposes, that’s all. And they can intermingle, mix, go into totally different directions and still make sense as a whole.

So, I personally think that Sanjuro’s post raises a good question, and something that also I would be pretty interested in exploring further. I am in no way knowledgeable about Japanese cultural symbols, either, but here is what I have got to offer.

The Gate, we must remember, is not just any gate but the capital city’s mighty Rashomon, a symbol in some ways of Japan itself. Akutagawa, it has been argued, depicted the famous gate in disrepair to symbolise a moral decline that he saw as taking place in the society around him at the time when he wrote the piece (I’m afraid that I don’t have a reference at hand now).

Kurosawa, you could argue, may have had something more specific in mind, considering the film’s immediate post-war timing (it was actually originally planned for 1948). More specifically, you could say that the Rashomon in the film symbolises the state in which the Japanese society found itself during the post-war years.

Yoshimito (189) very briefly touches on the idea that the film on some level could be seen as dealing with the post-war conditions in Japan. James S. Davidson’s “Memory of Defeat in Japan: A Reappraisal of Rashomon” (again, I’m afraid, in Rashomon) talks about this in more length, and suggests that any contemporary member of the audience in Japan would have made this link.

The commoner’s actions in consuming the Rashomon (as I earlier worded it) may, indeed, well say something about what his type of pessimistic cynics were doing to the society as a whole at a time when, Kurosawa might have argued, optimism and humanism were more strongly needed.

While not quite a symbol, you could nevertheless say that the overall war, destruction and devastation that is referred to but never shown, also has a very direct point of reference. This seems to have escaped George Barbarow (reprinted once again in Rashomon), who argued that there

should be and could be better evidence that this is a time of disasters … What is needed in the film is cinematic evidence having the cogency of the dramatic evidence in the wonderfully articulate beginnings of Macbeth and Hamlet. It is all very well to start with an excellent rain-storm, but rain is not an earthquake and a sword fight is not a war, and a movie-maker who must rely on a direct title to make a main point is not a master. (147)

Barbarow’s oversight here is perhaps that he didn’t ask why these things actually weren’t shown in the film. Which, if we took into defending the interpretation of Rashomon as a commentary on post-war Japan, would simply be that had Kurosawa shown armies clashing and 12th century peasants running away from an earthquake, he would have lessened the impact of the reference.

This is, of course, putting aside the issue of the budget. Somewhat related to this, Yoshimoto also notes that Kurosawa at least at some point wanted to open the film with a large crowd engaged in black market activity in front of Rashomon: “the rain starts to fall, and as it becomes a downpour, the crowd run away in all directions; the three characters take shelter under the gate and start telling stories about the rape and murder incident.” (189) I wonder if this was cut for budget reasons? The film was, after all, sold to Daei with the idea that it would be cheap: three locations, a handful of actors.

The rain I would take to stand in direct contrast with the almost disturbingly bright sunlight that we have in the forest and the courtyard scenes. Rain heightens emotions, whereas bright sunlight (at least to me) tends to have a dulling effect. What to me the rain therefore symbolises is the downpour of disturbed emotions that we witness at the gate, as opposed to the very clinical and I would say theatrical set of emotions in the other scenes. But this is just me, and just one interpretation. Perhaps you could also think about the rain’s function as covering or hiding something, while a direct sunlight makes everything visible, a bit like a bright spotlight they use in interrogation rooms.

The patterns of light and shadow, meanwhile, are perhaps there to obscure that very division between light and shadow, or reality and fiction, objectivity and subjectivity. While beautiful, there is also something ultimately disturbing about those patterns. I’m sure someone has written a lengthy treatment on this, but I can’t right now find it. I’ll come back to this if it resurfaces.

I pretty much think that you have written what I would have written in what you wrote about the forest. For some reason, the forest also makes me think of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

I’m also glad that you brought up the scene where the wife kneels next to the stream, it is perhaps my favourite in the movie. I never thought about it, but you are right that there may be is something really interesting going on regarding water in this film.

Water is traditionally (although I don’t know if this is true of Japan) seen as a feminine element, and symbolises (among other things) purification, life and fertility. Perhaps if we pick “purification” for our interpretive purposes, you could argue (and you kind of already did) that the wife’s sitting next to the stream before the rape scene goes on to highlight the purity and the beauty that she is about to lose. A stream, of course, also has a relatively strong sexual connotation.

Her later trying to drown herself could then be taken as an act of purification, her (attempt at) cleansing of herself of the evil that has been done to her.

As a notorious bandit, Tajomaru is meanwhile beyond the point of return and can no more be purified by water — he is, instead, poisoned by it.

Perhaps a bit far-fetched, but there you go.

I’m sure that there are more. Yoshimoto, for example, mentions the repetition of number three in the film: there are three locations, which each have three principal characters, and a three days have passed between the courtyard scenes and the Rashomon scenes, plus there are three Chinese characters at the top of the gate: Ra-sho-mon. (185) Yoshimoto then goes on to talk about symmetry and vertical and horizontal composition in the movie — there’s some really good stuff there, the more I re-read Yoshimoto, the more I love that book.

The next time I watch the film, which I am hoping to do today or tomorrow, I shall try to pay particular attention to potential symbols and see if I can spot anything else.

7 May 2008

I gave the film another go, and while I must say that I couldn’t really pick up any possible new symbols to speak of, while I was watching it I had Richie’s commentary turned on and he talked about compositional triangles.

Jeremy probably knows more about this than I do, but Richie notes that triangular compositions are generally used to communicate uncertainty and conflict, as opposed to squares (calmness) and circles (togetherness).

As you watch the film with this in mind, you indeed notice quite a number of triangles. I didn’t want to spend too much time capturing them, so here’s just one of them, and probably the most pronounced of them all:

And here’s another, something that Richie didn’t point out but what came to me while staring at the cover of the Criterion DVD case just now:

Isn’t that kind of a triangle, right there in the post-titles opening shot?

A triangle, of course, is yet another one of those “threes” that I earlier noted Yoshimoto talks about. I also spotted another three — not only is the time that elapsed between the courtyard scenes and the Rashomon scenes three days, but it was also three days between the time when the forest scenes supposedly took place and the courtyard scenes (this, according to the priest’s testimony).

It also came to me that a downwards pointing triangle is in fact the alchemical symbol of water. I don’t know how well Kurosawa knew his hermetic sciences, but funnily enough, there is your water again. And I think that an upwards pointing triangle is meanwhile the alchemical symbol of fire — there’s your contrast between the rain and the sun. I wouldn’t go around saying that Kurosawa intended this, but it’s just an interesting coincidence.

7 May 2008

I find the symbolism interesting and wish to get to that soon.

I do agree the square offers calmness, as its design is one of stability, ideally its for importance and purpose. The circle I guess I could go with togetherness, but typically its used to provoke sentimentality. Anyways these are minor tweaks on the same thing.

Back to the triangle, I’m not in the understand or feeling that a triangle represents uncertainty or conflict. The triangle is used to represent grouping, giving emphasis to the character that takes the highest apex as the owner of the group.

I used google for this, and if I’m not mistaken a painting from Raphael

You could also study the Roman’s and Egyptian use of the triangle for example, in which case its always of means of grouping, so to show unity, and never conflict. More importantly the study of its use in the christian religion, in which the vast majority of early art principles where governed by.

Although you may be able to ignore this for other directors, Kurosawa was a skilled artist. Certainly his use of shapes goes directly with the painting principles of the shapes from the past, rather then any hybrid use of them in movies.

I just happen to like Richie’s mention of conflict, I havent had to chance to hear what he said, but I think he is lacking depth to the bandits role in the shape. Although he is ultimately correct, I think he is associating the conflict with the shape, rather then the bandits role in it.

To me I see in Vili’s first screen shot the group of the wife and husband.

The husband being at the peak, claims ownership of all with in the shape.

This by itself is no conflict and I’m not aware of the triangle ever attempting to be use for so.

However the bandits role in this appears to be a means of exterior grouping. We have a internal battle between the wife and husband, but the bandit it the only cause of the internal battle as well as the foundation of triangular grouping.

Where at first the husband has is wife on display, with him being at the bottom(I still prefer her to be considered a prize, rather then a person, without intended to demeaning women or group them into this discussion), he now has her on the ground and staking claim to her.

What the bandit is doing is forcibly grouping himself with the wife and husband, as in reality he really does. This is the conflict. Its the bandits role in the shape, rather then the shape itself.

Also as Vili second picture shows, to me at least its again a means of grouping all those under the gate together, rather then presenting conflict, but I suppose that feeling is easily debatable.

7 May 2008

Fascinating reading from Jeremy and Vili both. Jeremy’s explanation of triangular shapes in paintings certainly seems to make sense here, and your analysis, Jeremy, of the first screenshot is fascinating. It made me think of various paintings I have seen which correspond to what you said; William Blake’s Ancient of Days, for example, which sees a creator figure at the peak claiming ownership, in your words, of all that lies within his compasses (the material universe, in this case). There is also Blake’s Adam and Eve, where Blake’s Satan stands at the peak and thus claims ownership of the two human figures (the circular shape of the bower itself, by contrast, suggesting harmony).

At the same time, I can certainly see the sense of the triangle as suggesting uncertainty or conflict, as Vili says, at least on the thematic level and in the relationships between characters. Moving away from Rashomon, Seven Samurai’s Kikuchiyo is a character whose identity seems uncertain. At times he seems to belong to the peasants, at other times to be a true samurai, and even at times a bandit (in the scene where he goes to get a gun, for example, the bandit at first takes him for one of their own). And of course Kikuchiyo is represented on the banner by a triangle, in contrast to the other samurai.

Getting back to Rashomon at last, I take back my earlier speculations about the role of water – I do think that Vili is right on the mark when he writes about how Tajomaru is beyond redemption and therefore cannot be purified by water.

Speaking of threes, the Rashomon Film Club so far has seemed a three hander – I would say a two-hander at the risk of seeming falsely modest, but the fact is I’ve learned an immense amount already from Vili and Jeremy, and not just about Rashomon. Thanks for all the effort you have both put into this, and I hope that some of the other regulars to the forum will contribute some ideas soon (hint hint).

8 May 2008

Thanks for your responses, guys. Considering Kurosawa’s background in painting and his love of that art form, I think that insights from the world of painting may well be quite directly relevant to Kurosawa’s works.

Jeremy may be right about Richie making too direct an assumption about the triangle. It may also well be my misunderstanding or mishearing, of course, but if it’s Richie’s then I don’t think that it would be the first one in his commentary. There are a few other details that he gets wrong during his narration, which does somewhat lessen his credibility there.

While I personally quite enjoy Richie’s level of devotion and fascination towards Kurosawa here and in his written works, I think that he has the tendency to get so immersed and excited about what he is doing that he doesn’t always remember to check the details about what he is talking about. But I know that I’m often guilty of the same thing, myself.

Richie also notes in his commentary how, after the woodcutter’s second story, there suddenly appear many diagonal objects in the framing, and how this in Kurosawa stands for change. This is again an interesting observation (albeit one that I can’t verify or refute at the moment), but as a whole it just left me wondering why those diagonals weren’t any longer simply parts of triangles to Richie.

In fact, all I pretty much saw in the final scene was more triangles, but of a different shape than before. Throughout most of the film, it seemed to me that the triangles were pointing vertically either upwards or (less frequently) downwards. After the woodcutter’s story the triangles that I saw in the final scene were more of the type that pointed horizontally either left or right. But I would have to watch the film again to really concentrate on this.

Sanjuro’s point about Kikuchiyo is excellent. I guess we’ll need to keep an eye on triangles as we go through Kurosawa’s oeuvre in the coming three years.

9 May 2008

A correction to what I wrote earlier.

I think that I got the chronology wrong, or actually I think that I either misunderstood what Yoshimoto wrote or Yoshimoto got it wrong. (I am currently at yet another airport, and don’t have Yoshimoto with me, so I can’t check. I’m travelling for the next week or so, but will do my best to keep up with the news and the forums here.)

You see, three days passed between the day when the priest fleetingly met the two travellers, and the time of the trials. The priest tells this at the courtyard.

Three days have also passed between the rain at the Rashomon gate and the time when the woodcutter found the body. His “It was three days ago” does not refer to the trials (as I previously claimed) but to the events that he is about to narrate. This is towards the beginning of the film, just before he starts his first account.

Assuming that the husband and wife didn’t travel for more than one day, this means that the priest’s meeting with the victims and the woodcutter’s discovery happened on the same day. It also means that the trial took place earlier on the day of the Rashomon scenes.

Which explains why the woodcutter and the priest, who don’t seem to know each other too well, are still together. I actually started to wonder why they were still together if it was three days ago that the trials took place as I claimed above. The answer is that it wasn’t, it’s still the same day. They are probably on their way from the official proceedings, and happened to take the same route and be caught by the same rain.

Which might also give us an explanation as for why we aren’t told what the official verdict of the trials was. And why the priest and the woodcutter are so affected by the events. Maybe the judge is still thinking. As are the two others.

Unrelated to this, but related to the theme of symbols, what would you make of the bow, the quiver and the arrows?

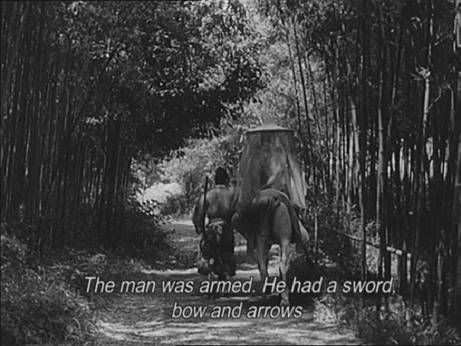

They have no direct function in the story, but are nevertheless quite prominently displayed in more than a few occasions. It is something that the husband is in possession of on the road, that he later leaves with his wife. The next time we see them is when Tajomaru is caught (in terms of the story’s chronology, that is), i.e. they are now in Tajomaru’s possession. They are also quite visibly displayed in Tajomaru’s court scenes.

Gotta catch my flight now.

9 May 2008

I haven’t given any thought to the bow and arrows. As you indicate they serve no function in the plot and that’s probably why I’ve overlooked them; I’ll have a look at the scenes soon and see if anything comes to mind.

The sword, the dagger, and the ropes I had thought about but I didn’t come up with anything beyond the obvious so I didn’t think it worth mentioning. But since I have brought them up, the sword, apart from being symbol of might, is obviously a phallic symbol in the scene where Tajomaru receives his fist vision of the wife; the dagger is often the weapon of a thief, and symbol of treachery and murder, as opposed to the nobility of the sword, and may also be here; the literal function of the ropes for binding seems to match their symbollic function.

Actually, I just had a look at my dictionary of symbolism and while there’s nothing about a bow it does mention that the arrow is for psychoanalysists the symbol of phallic sadism. Interesting thing for the husband to be carrying around. Don’t know if Kurosawa intended that, though. The dictionary also notes: “The tradition that a single arrow can be easily broken while a bundle of them holds strong, symbolizes strength through unity.” Now that’s another story.

10 May 2008

Yeah, you got me a bit confused Vili, as I always assumed the time period under the gate was only shortly after the court hearing and before a known verdict.

I like what sanjuro wrote, but I dont think at any point the weapons are giving much weight. If so certain things would be out of balance. Although I cant deny they are giving rather large visual weight.

14 May 2008

A very interesting discussion – I don’t know that I have anything new or especially insightful to add, and I may just display my talent for pointing out the obvious, but here goes:

With respect to the gate and its symbolism, AK obviously had a penchant for depicting structures that are in tatters and ruins – I think for example of the slums of ‘Ikiru,’ ‘Stray Dog,’ ‘The Lower Depths,’ and ‘Dodeskaden’; the bombed out structures and ruins of ‘One Wonderful Sunday,’ ‘The Bad Sleep Well,’ and ‘Madadayo’; and the castle ruins of ‘Ran’ and ‘Throne of Blood.’ Stephen Prince in particular I believe speaks of AK’s interest in contemplating what humankind must do in the face of societal decay and in particular to his time and place, what the Japanese needed to do in the aftermath of the moral and physical destruction of WW2. The ruined city gate would seem to externally symbolize this destruction and the need for moral and physical reconstruction. (I can’t help but consider, too, the destruction that AK himself witnessed, both during WW2 and during the Great Earthquake of 1923, and how this must have informed his obsession with such imagery.)

24 May 2008

That’s a good point about Kurosawa’s interest in decay and destruction, Andrew!

There is a mention of this, and a lot of other symbolism discussed in Keiko I. McDonald’s “The Dialectic of Light and Darkness in Kurosawa’s Rashomon“, which is the last essay in the Rashomon book. The fact that it is the last one explains why I am mentioning it only now — I only got there about a week ago! In any case, as the title implies, one of McDonald’s major concerns is darkness and light, which is what Sanjuro was wondering about in the opening post of this thread.

McDonald sees the rain at the Rashomon gate to stand for the “chaos prevailing in the [12th century] world”. She also makes an interesting note about the gargoyle and the signboard which, despite of the ruined state of the gate, are impact. In her view, the “integrity of these two religious symbols implies that religion has not been completely destroyed but, in fact, holds out a potential for the restoration of order”. I am personally not at all sure if I understand why the signboard is a religious symbol. Can anyone help me here?

McDonald considers the movie’s central problem as the following: “Is man’s nature essentially rational or impulsive, good or bad?” In connection with this, she sees light and darkness in Rashomon to symbolise not only good and evil but on another level also to stand for reason (light) and impulsiveness (darkness). She argues that Kurosawa treats darkness in the film “as negative until the final sequence of the film because Kurosawa presents impulses as deviations from man’s moral consciousness.”

McDonald considers the hats that the woodcutter finds in his first account as “important social symbols”, whereas the amulet case for her stands for “man’s adherence to religion”. The torn rope, meanwhile, symbolises liberation, and therefore “the abandoned social adornment symbolize the elimination of layers of the social mask, hence, the outer self”. In other words, “what happened to the woodcutter, the samurai, his wife, and the thief in the forest is, on a symbolic level, a centripetal regression into the inner self.”

She furthermore notes that the woodcutter’s axe can be read as symbolising control, and the fact that he drops it when seeing the husband’s body “externalizes his loss of control”, which then assumedly leads him into stealing the dagger.

She then observes a similar loss of control when the wife is trying to fight Tajomaru. In McDonald’s view, “Kurosawa elaborately cinematizes her moral dilemma through the juxtaposition of light and darkness.” The fact that the wife at the end of this scene first stares at the sun is, in McDonald’s view, the wife’s attempt to suppress her impulse through reason, which she fails at, and in closing her eyes and therefore symbolically moving into darkness she loses her reason and gives into temptation and impulse.

The forest, of course, is the provider of shade and therefore, in McDonald’s interpretation, the domain of impulsiveness, which manifests itself as what we would see as cowardice. As pointed out, however, they have let go of the social and religious layers that are normally guiding them, and actually function in the forest as purely themselves. In contrast to this, they are exposed to the bright sunlight at the police station, therefore again functioning as members of society.

What I take McDonald to indicate with this, but what she does not seem to straightforwardly say at any point, is that the source of the differences in the characters’ testimonies is the result of this contrast. In other words, they have to correspond to social expectations and reason when giving their testimonies, even if the actions themselves in the shaded forest were not guided by those same principles, but rather the impulses of their actual inner selves.

At this point I must say that there is much more to McDonald’s essay in terms of symbolism — she touches on a lot of issues ranging from the characters’ clothes to the camera work and what it at different points in her view comes to symbolise. Rather than rewriting her whole essay here, however, I only want to present her central argument.

As noted earlier, McDonald argues that Kurosawa treats darkness in the film “as negative until the final sequence of the film.” The final sequence is dealt at the end of the essay, and instead of paraphrasing, let me quote the last three paragraphs for those of you who do not have the book:

After the finale of traditional Japanese music, the woodcutter leaves the gate into the sunlight, with the infant in his arms. It is clear, from what we have observed, that the symbolic transition from darkness to light signifies that altruism offers a potential for harmony even in the fragmented world of Rashomon. At the same time this transition signifies that man’s nature is melioristic as found in the woodcutter’s behavior.

However, the last two shots significantly modify this critical deduction. First, Kurosawa presents a long shot from behind the woodcutter as he walks into the sunlight in vivid contrast to the shadow over the gate. Then the camera swiftly moves to a long shot of the woodcutter from the opposite angle. As he walks toward the camera, he stops and bows to the priest, beaming with happiness. However, despite the woodcutter’s magnificent display of optimism, we are visually deluded, for now we are given the impression that the woodcutter is walking into the shadow while the whole gate and the clear sky come into frame behind him.

This reversal of the light and darkness, the shadow and sunlight, which has hitherto been neglected by Kurosawa’s critics, seems to deny the optimistic tone with which most viewers see the film end. Rather, it stresses the difficulty of maintaining a melioristic stance in the fragmented world. Concerning the ending of Rashomon, Kurosawa himself says that he wanted to present gigantic columns of clouds (cumulo nimbus) above the gate, but they never appeared during the shooting of the final scene. The image of cumulo nimbus predicting approaching rain, though an external datum, serves as another justification for supporting the relativity of man’s nature as the film’s final implication.

25 May 2008

There are some fascinating points here. I do find her interpretation of the rain, the amulet case and certain other symbols to be quite convincing, and I also think that the film is very much concerned with religion and morality and the inner self that goes astray when it does not have religion or social values to guide it. I’ll say more about this in a couple of later posts that I need to get some screen shots for. For now, I had a look again at the last couple of shots and find it interesting that there is a kind of reversal – the woodcutter leaving the gate walking into sunlight, then in the next shot away from the sunlight into shadow (the gate in these shots seems to be a kind of window or portal from one state into another). However, I think it is important that Kurosawa lights the woodcutter’s face in such a way that he seems to carry the light with him as he enters the world of shadows at the end. I don’t think Kurosawa would have left us with a shot of the woodcutter walking away towards a brightly lit horizon – this would have been too cliched to bear. Rather, I see the first shot mentioned as representative of a move away from the shadow and confusion of doubt and moral uncertainty, but it cannot last, for as the next shot indicates the world is a place of shadows. There is then an adjustment of focus in the last shot, but the way Kurosawa shoots Shimura and the way he lights his form suggests to me that the woodcutter is carrying his goodness with him back out into the world, and the gate, now framed as a place of light, has become the site of his moral regeneration. The gate, in other words, now serves not as a stopping place but as a portal from one state to another. I would like to include a pic of the last shot to illustrate my point but I need to work out how and where to store images on the web.

25 May 2008

Ok, I’ll try to add the image here.

Sorry, have wasted an enormous amount of time trying to add an image from photobucket. Despite having resized the photo on said site so that it appears small, it still appears here as enormous, spilling over the edge of the message board window. Oh well, I give up.

26 May 2008

Again, an interesting take on the last scene!

Sanjuro wrote: Despite having resized the photo on said site so that it appears small, it still appears here as enormous, spilling over the edge of the message board window. Oh well, I give up.

The paragraph width is 530 pixels, so your photo’s width should be less than that. I don’t know how Photobucket functions, but it may be a good idea to resize before uploading.

I also took a look at different methods of allowing image uploads at akirakurosawa.info, but it seems that in order to accomplish that (if at all securely possible) I will first need to update the website software itself, which is a bit more work than I am currently able to undertake.

26 May 2008

This is just a test to see if pix works. Sorry if I’m taking up space here.

26 May 2008

I did manage to find a few more instances of symbolism to mention, and thanks to Vili’s help I should (hopefully) be able to use a few stills to illustrate the points. As usual I don’t really have much time to put my thoughts into proper order or to revise what I write but I’ll do my best. The following might be familiar to those who have read essays on Rashomon’s symbolism. If so, apologies for covering what is probably well-trodden ground (I haven’t read anything on this topic myself).

I have already mentioned the Gate and there’s been a consensus (I think) about what it stands for. What did strike me when I had another look at the gate scenes are the remarkable pillars which hold up the structure. If the gate stands for civilisation, the pillars may be the very values (particularly religious and moral values) which are its mainstays. It is not just pillars, in fact, that Kurosawa seems to imbue with symbolic meaning but upright shapes in general. But to begin with the pillars…

Pillars, then, stand for moral right. Within the gate, pillars stand strong though the outer shell is breaking apart. Without the gate, we see a fallen pillar. This is the place from where the commoner emerges. If the rain symbolises travails and the mud the muddying of moral clarity, it is no surprise that the commoner seems to emerge out of the very mud – his element being the morass. The moment the commoner arrives, he crosses the space of a fallen pillar, the pillar standing for moral collapse. Though he does not bring the tale with him, I believe that he is a representative figure (I will try to argue as much in another post, time permitting) who comes to stand for one side of the debate the film sets up (the other figure being the priest). Therefore it is significant that with his arrival we glimpse a pillar fallen in the mud.

An interesting side point here is that during the credits sequence Kurosawa’s name is superimposed over one of the gate pillars – could he perhaps be setting himself up not just as an artist but as a moral teacher?

It is not just pillars that stand for moral uprightness, it is also the priest himself. The priest is himself a kind of upright figure – he is tall and lean, physically reminiscent of one of the pillars, of course standing for moral righteousness. Appropriately, he carries a staff (which we see in the scene where he walks past the husband and wife). In the early gate scenes, the woodcutter seems at one with the priest – Kurosawa emphasises their noble upright stance and shared indignation at the crime (the fact that their heads are bowed does not alter the fact that Kurosawa emphasises their linearity). As the tale unfolds, though, the woodcutter loses his upright and dignified stance and becomes more like the commoner (even when he hides his face, or when his face registers shock, he seems morally indignant in the early scenes, more objective, able to judge; not so later on). Physically, the commoner seems the opposite of the priest – he appears crooked, he is often stooped, and as the tales are told and the priest’s argument of faith becomes increasingly weakened, the woodcutter begins to resemble the commoner more and more. The priest, too, is affected by the import of the tales and by the mockery of the commoner – in some of the later scenes he is seen to lean against the pillars; he loses his uprightness. The symbolism should be obvious – he is seeking moral support.

Reminiscent of the pillars are the magnificent tree boles seen near what are presumably the less dense areas of the forest. We glimpse one of these early on in the woodcutter’s walk. There are also a couple in the celebrated scene where Tajomaru is sleeping. What is interesting is that the closer we get to the inner grove, the more tangled and less linear or upright the forest becomes; the visual echoes of the gate’s pillars disappear. These trees, therefore, may be seen as a marker of the outer edge of the forest, a place to some extent ordered and managed by people.

Another kind of upright can be glimpsed in the scene where the husband and wife cross paths with the priest. The road they are followed seems densely “fenced” by tall, thin upright stalks (bamboo?). This would seem to be representative of the strict, narrow path they must walk through life as spouses.

If all goes well, there’ll be a few pics below to further illustrate the points.

One of the Gate’s pillars. Perhaps Kurosawa remembering the imperative “Benefit all mankind”.

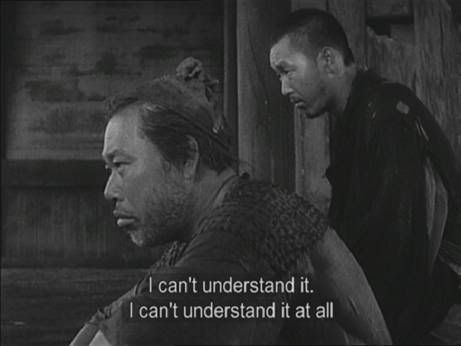

The woodcutter and the priest flanked by pillars, protected by moral right.

The woodcutter at one with the priest – Kurosawa emphasises their upright stance and nobility.

The commoner crossing the muddy ground, with a fallen pillar in the foreground – moral collapse.

One of the magnificent tree boles, every bit as impressive as the huge upright pillars of the gate. Such trees seem to be found on the outer, less dense parts of the forest, and appear to stand for stability and the normative. Towards in the inner grove, there is no such linearity and uprightness.

Tajomaru at the foot of one of the huge tree boles. Tajomaru’s placement is interesting, suggesting that even here, on the edge of civilisation, far from the tangles of the inner forest, evil can lurk.

The woodcutter distanced from the priest and thus from right. Note the diagonal beam that seems to tear through the very scene itself, obscuring the uprights. At this point in the debate, the woodcutter moves closer to the perspective of the commoner and thus further from right.

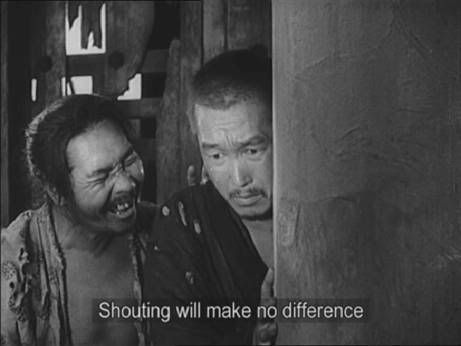

The priest clutching at the support of the pillar as his faith is attacked. Note the resemblance between the commoner’s cracked and gapped teeth and the dilapidated wall of the gate behind him. The priest, in contrast, is tall and lean, seemingly like the pillars that hold up the structure.

The triumph of the commoner. Tosses the wood onto the fire as the priest clutches for moral support and the woodcutter bows his head in shame.

The husband and wife following the straight and narrow path, hemmed in by pieces of bamboo(?). They will be led away from the straight road and into temptation. The priest, in the scene where he glimpses the husband and wife, is seen to carry a staff of wood, standing for his moral uprightness.

27 May 2008

No problem, Sanjuro. Good to see that you got it working!

28 May 2008

I cant offer anything on subject, but if anyone here has a video or have a large amount of photos they cant host elsewhere. I have a large server that I will lend for the service.

30 May 2008

That’s a very interesting post, Sanjuro! (And one that, unfortunately, initially got picked up by the spam filter. I am going to update the website software today, with the hope that it would stop that happening.)

The idea of the pillars standing for moral values is intriguing, and I think that you may well be onto something. The resemblance of the gate’s pillars and the tree trunks found at the “edge of civilization” (but not at the “heart of wilderness”) is also a very interesting, and true.

The trees in the thick of the forest, meanwhile, really seem to be pointing everywhere except for directly upwards!

Perhaps there is also a connection with the diagonal shapes that I earlier mentioned (following Richie) to be increasingly appearing towards the end of the film. The upright vertical pillars, trees and postures becoming diagonal or leaning could maybe be seen to symbolise the woodcutter’s move towards the commoner, which you pointed out.

It is also interesting that the ending, of course, returns us and the woodcutter to pronouncedly vertical lines. In the final shot, the gate rises majestically on the background (with all the vertical structures seemingly having disappeared), while the woodcutter’s gaze moves from the baby in his hands towards the sky, thus creating a clear vertical movement.

With your post in mind, it would perhaps be interesting to look also at the courtyard scenes and the varying postures adopted by the characters when they give their accounts. It would seem to me that each of them struggle at one point or another to maintain a good, upwards pointing posture, but that they all fail in some way or another. This is, however, only a memory that I have and not actually based on closely watching the scenes with verticality in mind.

Thanks for the post, Sanjuro! I had never really thought about the pillars in connection with other vertical shapes in the film, so it was a real treat to read your post.

31 May 2008

It seems the spam filter has a thing for my posts. I’m relieved to see it was rescued, though some of the text seems a little garbled. Reading through it again, I’m not sure how much Kurosawa would have been aware of these details on a conscious level (presuming there is any verity to the idea that the verticals stand for something), but that’s a thing about an artist being focused on a work – even the smallest things reflect that vision.

5 July 2010

These posts help inspire a paper I did for Rashomon in a film class earlier this year. I’ve posted it at http://www.newsummer.com/classes/rashomon.html . I’d be pleased to receive feedback.

5 July 2010

Michael, thats an excellent essay, really thought provoking. I hope you post the whole thing here for a discussion when we come around to Rashomon again. Have you read D.P Martinez’s book Remaking Kurosawa? Your analysis has quite a lot in common with hers – not in terms of metaphor, but in emphasizing post war guilt and the role of the baby.

Incidentally, I saw Rashomon two weeks ago for the first time on the big screen – the wonderful new restoration. It made me realise just how much is lost watching films on dvd, even with a decent screen – I was completely enraptured by it, I saw so much I missed before. The scene with the medium in particular is stunning on the big screen, I felt a chill run down my spine watching it that I never experienced on my other viewings.

6 July 2010

I can only agree with Ugetsu — that’s an excellent essay. And the underlying idea is indeed somewhat similar to what Martinez argues for in Remaking Kurosawa, so you might be interested in checking that out, although your approaches obviously differ.

I find the idea you propose very interesting that the three characters under the gate could be “counterparts to the three players in the crimes … the conscience of the samurai, the wife and the bandit, perhaps as representations of the consequences of what transpired earlier (in the past) in the forest. In any event, we find them at Rashomon, a sort of purgatory, in the rain, awaiting their fates.” The three are often talked about in terms of their relationship to the audience and the film (you could argue that the audience, the director and the film are represented by the three characters, and the film is really about, well, films) but I don’t off the top of my head remember a connection like yours drawn between them and the three characters of the main story. That’s a really interesting linking.

15 July 2010

Ugetsu posted,

“Incidentally, I saw Rashomon two weeks ago for the first time on the big screen – the wonderful new restoration. It made me realise just how much is lost watching films on dvd, even with a decent screen – I was completely enraptured by it, I saw so much I missed before. The scene with the medium in particular is stunning on the big screen, I felt a chill run down my spine watching it that I never experienced on my other viewings. “

Wow. You are so right! In fact, the medium could be seen as almost comical on a small screen. Imagine watching on an I-pod. How easily dismissed, right? Some little figure with poorly-applied lipstick whirling about yabbling about what?

On the big screen, in film…it was….beautiful, alarming…really eerie! I have never been one to believe in anything of the sort, yet found myself understanding COMPLETELY how compellingly real one might experience an encounter with the supernatural like that!

I saw the restored version on the big screen a couple years back, and agree heartily with Ugetsu that there is something lost on the little screen.

That thing is scale.

It is one of the most important of tools in the artist’ s bag of tricks. Ask Claes Oldenburg, (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dropped_cone_Cologne.jpg) or any filmmaker.

Scale is so…personal. We tend to feel protective and intimate toward the diminutive, and in awe of the huge. By extension, we may also feel a bit superior to the small, and inferior to the large. We may also more easily dismiss the minute and overvalue the big. I am guessing this all plays into the psychology of the Napoleon Complex, why tall people make more money than shorter people (on average) and why architecture was the “queen” of the arts-having to do with space, scale and size/proportional relationships.

In terms of symbolism, the gate of Rashomon is a powerful reminder of a loss of civility/civilization and moral authority. It is a brilliant thing-I believe Akutagawa and Kurosawa were seeing the same vision. The monumental, ruined gate represents: human civility, civilization, welcome, order and dignity-and in its ruined state represent the opposite: incivility, the collapse of civilization, hostility, disorder and chaos, and human corruption-all on a LARGE SCALE.

One of the reasons that I am so impressed by Kurosawa’s work is that the visual symbols of his films have such depth and profound meaning. Really, they never collapse in on themselves as artificial constructs. When symbols serve to create meaning, they are alive and you have high art…when symbols collapse into tired cliche’s, you have the unfortunate condition of second-rate art that ages badly.

Anyway, a shoutout to Ugetsu for bringing up SCALE as an important element of the filmmaker’s art.

16 July 2010

I found the medium laughable when I first saw the movie on a 19-inch television in the 1970s and thought it was due to cultural differences and my disbelief in direct communication of that sort with the dead that caused it, but after reading Coco’s post, I suspect differences of scale also played into it

Also, although the conclusions of the essay seem a little far-fetched before reading it, the arguments are elegantly made and well-supported. Anything that makes me appreciate Rashomon more is a plus in my book; out of all of his movies that I’ve seen, it’s the one I relate to least.

21 July 2010

coco

One of the reasons that I am so impressed by Kurosawa’s work is that the visual symbols of his films have such depth and profound meaning. Really, they never collapse in on themselves as artificial constructs. When symbols serve to create meaning, they are alive and you have high art…when symbols collapse into tired cliche’s, you have the unfortunate condition of second-rate art that ages badly.

Coco, thats a brilliant comment. I mentioned the scene with the medium, but that wasn’t the only scene I felt I was seeing for the first time. I really appreciated the scale of the Rashomon Gate set – it is an amazing set. I just wish, wish, that for the centenary there were some more cinema versions going around – I’ve only ever seen Rashomon and Ikiru in the cinema – I can only assume that the likes of Seven Samurai and Throne of Blood are unmissable on the big screen. Or maybe I should invest in a projector!

22 July 2010

Ugestu, I have been lucky enough to see Yojimbo on the big screen. Oh, it is amazing! The Michigan just did Rashomon again. (http://www.michtheater.org/summerclassics.php) But, there’s nothing else on.

You are so right….can you just imagine seeing Seven Samurai?

On a different, cheeseball note, a former student of mine is working on “Scream 4”. I’m actually quite proud of him!

11 February 2013

the bandit: the R complex of the brain; the reptile mind. fight or flight. survival. action.

the wife: the limbic system of the brain: human emotion. care.

the husband: the neocortex of the brain. reason. intellect. will.

13 February 2013

wildorchid – Welcome to the site. I have a question, though: Where does the woodcutter fit in, then? Rashomon has four POVs, not three.

26 March 2013

I’m only now seeing your comments on my Rashomon essay–nearly three years later! Thanks! I’m writing about it again for my class on the modern history of Japan. I’ll be reading over this thread again for any further thoughts.

5 January 2016

On the subject of triangles, look at the way Tajomaru’s legs are bent, subconsciously clutching his tsurugi when we first see him in his apparent flashback. That is a triangle in itself.

I decided to start this topic more to find out what ideas other people have than to offer anything meaningful myself, particularly after reading (in Prince I think it was) that whole books worth of essays have been written about the film’s symbolism. I don’t really have any background in interpreting literary or cinematic symbols but I do find it interesting to try to guess what they mean. In Rashomon Kurosawa seems to have applied a very conscious series of symbols and I’ve put together a few tentative thoughts below. The trouble that I do have, however, is that I lack any sort of background in Japanese culture and of course the meaning of symbols is at least in part culturally determined. Can anyone shed more light on what they think the main symbols of the film are and what they mean?

The Gate – is this perhaps representative of cultural or civilsed values, perhaps of civilisation itself? I can’t help but think of the way the commoner (a character who not only accepts but actually seems to embrace lying, a cynic and arguably a parasite) breaks pieces of wood from a structure that is already in ruins. Is there perhaps a contrast with the woodcutter (who cuts or gathers wood, thus contributing to society)?

The rain – I link this to the sort of afflictions the priest mentioned in the opening scene. Is it perhaps these given physical form? Or could it represent the lack of the sort of moral clarity insisted on by the priest, a clarity regained at the end, when the weather clears up and the woodcutter adopts the baby? A morass, then, created by lies and subjectivism. On the other hand, of course, in western culture rain oftens stands for cleansing and redemption, and ultimately that is what we get by the end of the movie.

The glade and the forest – Kurosawa gives us enough clues in Something Like an Autobiography for us to be able to guess what he intended. Of course, that does not mean that one has to slavishly accept the intentions of the artist. He says: “In the film, people going astray in the thicket of their hearts would wander into a wider wilderness, so I moved the setting to a large forest”. Is the central glade then the most egotistic part of our psyche, where we lie not just to others but to ourselves?

The stream and the pool.

In one of the film’s most beautiful scenes, the wife kneels (if memory serves) next to a stream that runs through the forest. The most obvious meaning of this seems to be of the beauty that can be found even in the heart of a moral wilderness. But I do get the feeling there is more to it – the scene comes just before the rape, and there does seem to be something deadly or duplicitous about water in the film (extending even to the hard rain which obscures everything beyond the gate itself, the point of refuge) – think of Tajomaru’s claim that the water he drank from was poisoned by a snake, and the wife’s attempt to drown herself in the pool.

Any thoughts about these and other symbols? (I would particularly like to hear if anyone can offer an interpretation of the patterns of light and shadow that Kurosawa built into the film’s forest scenes; beautiful as they are, they seem to me to have some kind of obscuring, hypnotic effect that again one associates with lack of moral clarity).