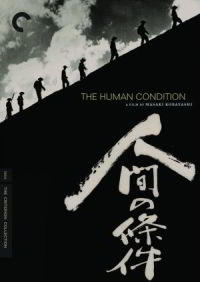

February’s Akira Kurosawa film club title is Masaki Kobayashi‘s epic film trilogy The Human Condition (人間の條件, Ningen no jōken), released between 1959 and 1961. The almost 10 hour long work follows the story of Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai), a Japanese pacifist with socialist leanings, as he navigates through World War II under the oppressive conditions imposed by the fascist totalitarian state. The individual films are titled No Greater Love, Road to Eternity and A Soldier’s Prayer.

February’s Akira Kurosawa film club title is Masaki Kobayashi‘s epic film trilogy The Human Condition (人間の條件, Ningen no jōken), released between 1959 and 1961. The almost 10 hour long work follows the story of Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai), a Japanese pacifist with socialist leanings, as he navigates through World War II under the oppressive conditions imposed by the fascist totalitarian state. The individual films are titled No Greater Love, Road to Eternity and A Soldier’s Prayer.

For a proper introduction to the films, I refer you to Philip Kemp’s essay, which is part of the Criterion set and can also be read online. It gives a good overview of the films’ background and spells out the trilogy’s themes and topics without going too deeply into the storyline.

Thematically, we have paired The Human Condition with January’s film club title Red Beard, and it would be interesting to hear how you think Kobayashi’s epic may have influenced or inspired Kurosawa.

The Human Condition is available as a Criterion (Region 1) DVD.

Next month, we will not be returning to a Kurosawa directed film but will start our short detour through Kurosawa’s Hollywood adventure, watching Runaway Train (Konchalovsky, 1985) in March and Tora! Tora! Tora! (Fleischer-Fukasaku-Masuda 1970) in April. For background reading on these films, I would highly recommend Hiroshi Tasogawa‘s excellent book on the subject, All the Emperor’s Men. It is one of the best Akira Kurosawa books out there.

We return to our regular programming in May with Dodesukaden. Information about the availability of all of these films, as well as the full Kurosawa film club schedule can be found here.

I finished the first film today and quite liked it. However, I was left with a couple of observations and thought that I’d drop them here in case anyone else has started going through the trilogy:

1) I found the framing in the film a little strange. What’s up with it?

Often the camera frames the on-screen characters in a way that makes them look like they are drowning. These shots are somewhere between a medium shot and a medium close up, with the frame cutting the characters off around their stomach area. Yet, plenty of space is left above these characters. It feels very uncomfortable, almost amateurish framing, but I wonder if it was done on purpose.

At least in a few cases it probably is, as characters move in ways that use the space better. But I would say that in a majority of cases, this is not true, as characters don’t move.

It is an interesting contrast to Kurosawa, who would probably have moved the camera to constantly re-frame as characters move around.

These shots are also typically given from low angles. In fact, there seemed to be very few high angle shots in the whole film. It keeps us grounded.

2) Does the content of the first film justify its length? I’m not sure that it does. It’s not a slow film, or at least my time passed nicely while watching it, but ultimately not that much happens, and the characters aren’t really developed that much either. As a three-and-a-half hour film, it could perhaps have included more?

Of course, it really is just the first third of the whole story, so perhaps we will be rewarded later for our patience.

3) With that said, the characters are quite one-dimensional.

4) And I’m not sure if Kaji is the most interesting point of view character here. I was wondering what the story would look like if seen primarily through the eyes of the young Chinese man who is trying to get flour to his sick mother and later ends up helping the prisoners escape.

5) Also, Japanese actors speaking Chinese didn’t really work for me, even if I don’t speak a word of Chinese myself.

6) But boy are the Japanese guards really strong! The people they attack are often hurt even when the guards are actually just waving their arms close to them and not making any contact. 😉

Anyway, all in all I did like it and look forward to continuing the story and seeing what happens to Kaji’s humanism.

By the way, I know that I’m a little behind with all the other discussions here but I hope to get to them soon.